Past

Gerald Jackson

I BUILD PYRAMIDS — STAIRWAYS TO HEAVEN

Mar. 15–Apr. 27, 2025

Gordon Robichaux is honored to present I BUILD PYRAMIDS — STAIRWAYS TO HEAVEN, Gerald Jackson’s second solo exhibition at the gallery and his most extensive to date. Installed across both of Gordon Robichaux’s spaces, the presentation features key artworks created between 1969 and 2025 that exemplify the artist’s multifarious creative practice. The exhibition’s title is inspired by a promotional business card Jackson produced and distributed with his name and phone number, printed alongside a mystical promise: I BUILD PYRAMIDS — STAIRWAYS TO HEAVEN.

Over the course of seven decades since he arrived in New York from his native Chicago, Jackson has actively responded to the social conditions he experienced throughout his life—poverty, racism, and violence—through a philosophical and conceptual approach to artmaking infused with poetry and politics. His artworks evidence these strategies, whether through his transformation of detritus into objects of beauty and significance; his use of existing cultural and spiritual languages to construct new, liberating mythologies; or his exploration of the power of color and light as agents of healing and transcendence. Throughout, Jackson has employed an expansive array of art-making strategies—painting, assemblage, photography, drawing, film, poetry, music, clothing, and performance—and made use of a variety of materials, which he frequently salvaged from the street, including unstretched fabric and canvas, bedsheets, Styrofoam, shredded paper, felt strapping, and wood “skid” shipping pallets.

Beginning in the early 1970s, and until his eviction in 2002, Jackson lived and worked—with minimal financial resources—in a large, raw commercial loft on the Bowery alongside industry, flophouses, bars, and a large, unhoused population. Over the years, Jackson has produced a series of works on paper that bear witness to his memories of the street. Here, scenes of violence, sex, money, drugs, and magical symbols of transcendence appear in dreamlike fields of saturated color, applied with watercolor and crayon. For Jackson, the Bowery encapsulated the harsh reality of American society and its failures, while also providing a place of refuge to explore his creative vision. In Downtown Manhattan, he also found freedom and inspiration within a pulsating community of artists and musicians, among them McArthur Binion, Peter Bradley, Ornette Coleman (Jackson’s roommate), David Hammons, Corrine Jennings, Lorraine O’Grady, Joe Overstreet, Bob Thompson, and Stanley Whitney. Within this context, Jackson developed a singular voice and prolific body of work that was supported and celebrated by his peers and exhibited sporadically—including at Allan Stone Gallery, Tribes Gallery, Rush Arts (curated by Jack Tilton), and Wilmer Jennings Gallery at Kenkeleba House in New York—but has come into greater view today in its scope, complexity, and radicality.

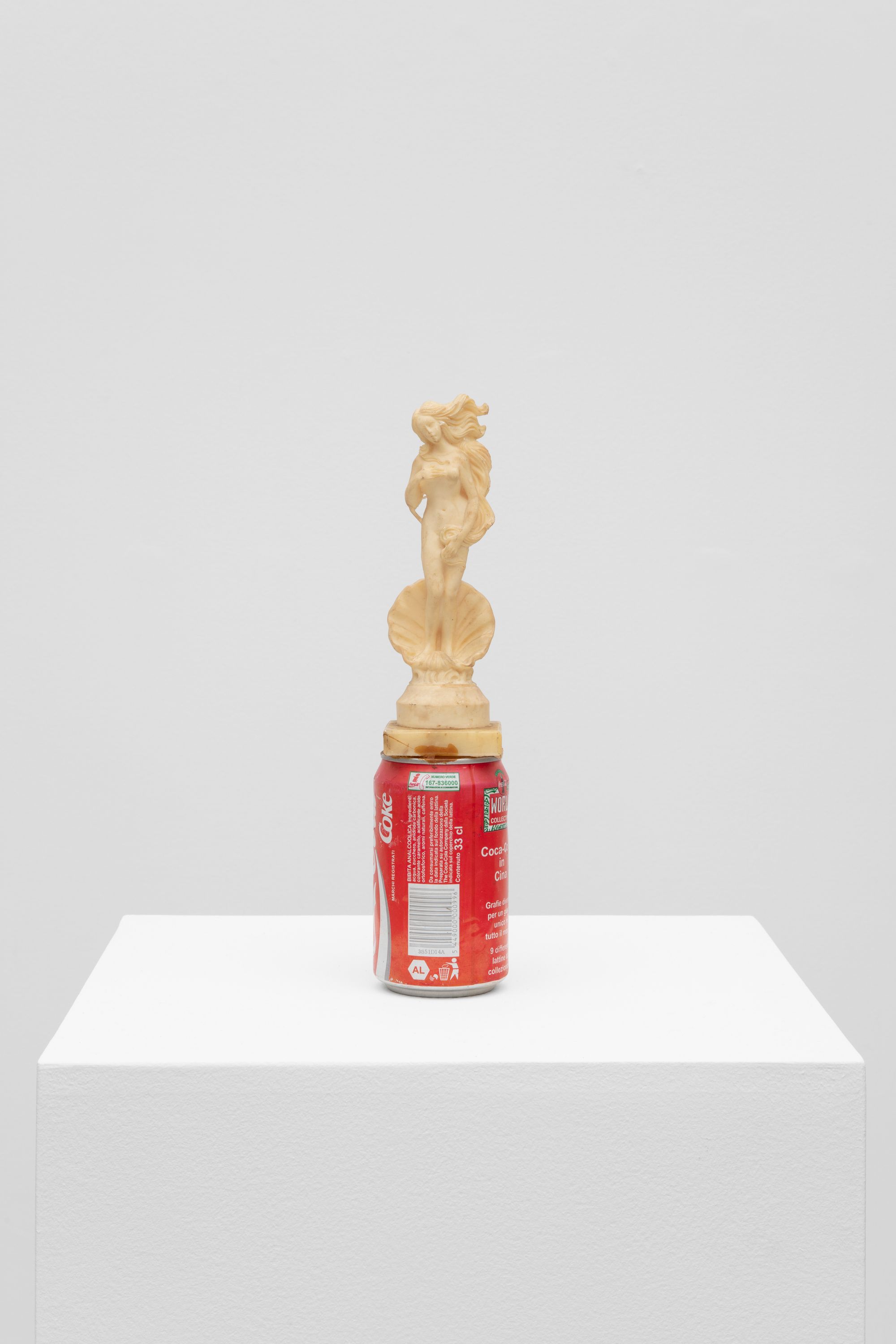

During the second half of the 1960s, following several years working primarily as an abstract painter, Jackson began incorporating figurative imagery and found objects into his work. His belief in the transformative, spiritual dimension of art is evident in the earliest artwork featured in the exhibition, an untitled figurative painting (1969) on a found, irregularly shaped panel, created with a thick, textured impasto. Jackson depicts a stylized figure—a goddess or Madonna—with a halo of rays emanating from the head and body that evokes a modern icon painting for veneration or spiritual invocation. Displayed nearby on pedestals, four small assemblages from the early 2000s take the form of miniature monuments featuring female subjects from canonical works of Western art history. The base of each sculpture comprises a red Coke can (a special edition celebrating the product’s ubiquity with text in Chinese, Russian, Arabic, or English) that functions as a classical pillar supporting a fragment of marble, crowned with a cheap plastic reproduction of an iconic artwork: Botticelli’s Venus, Michelangelo’s Pietà, and goddess figures from classical antiquity. Combining high and low culture, Western and non-Western languages, and various historical epochs, the diminutive monuments reverberate as enduring symbols of power and signification.

Jackson’s series of Skid works (1980s), two of which are on view in the exhibition, were created with shipping pallets and fragments of wood the artist collected from the street below his loft. While he initially scavenged and burned them for heat, Jackson recognized that the structure of the pallets resembled the reconfigured or deconstructed stretcher bars of a painting, prompting his varied responses to the form—as both a support and ground. Jackson nailed, stapled, wrapped, stretched and bound lengths of felt strapping, electrical wires, and canvas onto and around the bars; he painted and applied areas of vibrant, textured pigment and segments of broken wood to the surfaces; and he attached his own panel paintings to the assemblages. These hybrid objects evidence the artist’s sensitivity to materials and form, and his capacity to transform the marginal into profound objects of contemplation.

Since the 1970s, Jackson has developed his own vocabulary of spray-painted pictographs made with found and handmade stencils. He deploys the graphic images as optical patterns, which he layers across the surface of bedsheets, panels, stretched canvases, and garments. The recursive symbols evoke a kind of timeless and universal visual form of storytelling rooted in cultural and spiritual references both ancient and modern, such as prehistoric cave paintings, graffiti, and early video games. Images of stars, floral patterns, and characters from nursery rhymes collide with cobras, helicopters, missiles, and warriors. A pictograph of a bird invokes metaphysical powers—rebirth, healing, immortality—associated with the phoenix in classical antiquity and ancient Egypt, as well the holy spirit central to the mysteries of Christianity, and the Thunderbird in Native American mythology. Images of a humpbacked figure playing the flute call to mind Kokopelli, a trickster deity associated with music and fertility and venerated by a number of Indigenous cultures of the Southwest.

Throughout Jackson’s decades of artmaking, color has endured as a foundational social and political concern. He reflects, “I think that my experience growing up in America was really a black and white experience. The only color I think I really saw, that I thought was color, was on TV commercials: a different view of America—that America was in color and my world was in black and white.” For Jackson, color is inherently bound with experience and the possibility of empowerment and liberation. In an untitled text drawing on loose leaf paper (2025)—the most recent work in the exhibition—Jackson has composed a list of colors and their transformative attributes, such as wisdom, energy, power, which he found within the pages of the Bible. In his ongoing body of work dedicated to the colors blue and green, Jackson embraces their associative power (green for verdant earth and blue for sky and water) and their spiritual qualities, engaging a fundamental human connection to these pure and elementary colors, which cut across social constructs like race and class. A mixed-media work on a found metal sign (2021), on view in the smaller gallery, exemplifies these concerns. A photographic image of a Black couple in a moment of joyful embrace surrounded by a field of blue and green paint belies the object’s original function as an advertisement. In a succession of deft moves, Jackson subverted the ad and liberated the couple by collaging over the embossed Newport cigarette logo and resituated them within a symbolic landscape onto which he scrawled the phrase “Black Lives Matter.”

In a typed proposal for a monumental sculpture (2000), Jackson describes a “large temple…the size of the great Pyramid at Giza” constructed with “red, blue, and yellow glass or plastic (plexiglass)” that “shall meet the need of Humankind to reinforce its connection with the universe.” He goes on: “The connection shall be visibly and energetically expressed in the sun’s rays beaming through fields of color onto the surrounding landscape.” In a related text (2000) Jackson elaborates on the profound power of color and light to affect the human condition and “radiate healing frequencies.”

A kinetic work (early 2000s) encapsulates Jackson’s philosophy of aesthetics and metaphysics. Hanging on a pipe near the ceiling of the gallery, a blue plastic hanger functions as the armature for a mobile with objects suspended from shiny gift-wrapping ribbon. At the center of the constellation, five compact discs—labeled “Fugazi,” “Movie not good,” and “Spring ’05” by their previous owners—capture and reflect prismatic light. The discs are flanked by two vertical, metallic gold pagodas, each structure incorporating tiny bells and chimes onto which Jackson has strung a banner of Tibetan prayer flags; their colors represent the sky, space, air, wind, fire, water, and earth. Originally installed in the backroom of the artist’s home, the healing machine harnesses color, light, sound, and history with humble yet profound economy.

Gerald Jackson (b. 1936, Chicago) lives and works in Jersey City, New Jersey. In May 2025, Jackson will present his first exhibition in Europe, Keep Looking: Works from 1978–2025 (curated by Matthew Higgs) at Kienzle Art Foundation in Berlin. Recent solo exhibitions include those held at Gordon Robichaux (2025 and 2021), Parker Gallery and Marc Selwyn in Los Angeles (2022), and White Columns (2021) and Kenkeleba Gallery (2020) in New York.

Jackson’s history was outlined in an expansive—and essential—2012 interview with his friend, the artist Stanley Whitney, published as a part of BOMB Magazine’s ongoing Oral History Project, which is available on BOMB’s website.

After a stint in the army in the early 1960s, during which he further developed his skills as a marksman, Jackson relocated from his native Chicago to New York’s Lower East Side, where he encountered and became a part of a community of vanguard artists and jazz musicians centered around Slugs’ Saloon, a now-legendary jazz club on East 3rd Street active from the mid-1960s to 1972. Having pursued studies at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and later at the Brooklyn Museum Art School, Jackson began to exhibit his own work starting in the mid-1960s. He was represented by Allan Stone Gallery in New York from 1968 to 1990, and has had numerous exhibitions including at Strike Gallery, Rush Arts Gallery (curated by Jack Tilton), gallery onetwentyeight, and Tribes Gallery, New York.

His work has been included in a number of key group exhibitions including: A Decade of Acquisitions of Works on Paper—Part II, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles (2022); Afro-American Artists: New York and Boston, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (1970); Black Artists: Two Generations, Newark Museum (1971); JUS’JASS: Correlations of Painting and Afro-American Classical Music, Kenkeleba Gallery, New York (1983); The Black and White Show (curated by Lorraine O’Grady), Kenkeleba Gallery, New York (1983); Notation on Africanism, Archibald Arts, New York (1995); Something to Look Forward to (curated by Bill Hutson), Phillips Museum of Art, Lancaster, Pennsylvania (2004); and Short Distance to Now—Paintings from New York 1967–1975, Galerie Thomas Flor, Düsseldorf (2007), among others.

Recent reviews of Jackson’s exhibitions have been featured in The New York Times, The New Yorker, New York Magazine, Hyperallergic, and Frieze.

Jackson’s work is held in the collections of the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; the Museum of Modern Art, New York; the Studio Museum in Harlem, New York; and the Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY.

Install (17)

Works

Untitled

Found objects and adhesive

11.75 x 2.5 x 2.5 inches

c. early 2000s

Untitled (Colors in the Bible)

Japanese maker on paper

10.25 x 7.5 inches, 15.75 x 12.75 x 12.25 inches framed

2025

Untitled

Mixed media on panel

38 x 24.25 inches, 38.5 x 25 x 2 inches framed

1969

Untitled

Found objects and adhesive

11.75 x 2.5 x 2.5 inches

c. early 2000s

Untitled

Watercolor and ink on paper

13.75 x 10.25 inches, 15.75 x 12 x 1.25 inches framed

c. 2001

Untitled

Mixed media on styrofoam

35.75 x 40.5 inches, 36.75 x 41.5 x 2 inches framed