Past

Janet Olivia Henry

Six Decades

Nov. 3–Dec. 22, 2024

We are honored to present Janet Olivia Henry’s first solo exhibition at Gordon Robichaux, following the gallery’s presentation of the artist’s work at the Independent Art Fair in 2023; the inclusion of her art and graphic design in the celebrated exhibition Just Above Midtown: Changing Spaces at The Museum of Modern Art, New York in 2023; and Henry’s first solo exhibition in Los Angeles at STARS gallery this spring.

Installed across both of the gallery’s spaces, Janet Olivia Henry: Six Decades is the artist’s most comprehensive exhibition to date, evincing her commitment to an inventive, multifarious practice and the development of a singular visual language. In the larger gallery, the artist will present foundational early works: Juju Box sculptures comprised of small toys, trinkets, and personal effects collected and assembled during the 1970s alongside hanging anthropomorphic objects incorporating photographs, text, beadwork, Japanese knotting, and sewn and batted vinyl created during the 1980s. The second gallery will feature recent works, including hanging sculptures with dense clusters of colorful beads and narrative texts and a diorama of the artist in her studio constructed with Lego-like building blocks, a plastic doll, and toys.

Throughout, Henry employs a wide array of materials—miniatures, dolls, beads, vinyl, and shredded currency—and photographic processes, creative writing, and craft traditions including sewing, weaving, braiding, quilting, and jewelry-making. A lifelong educator and activist, she embraces storytelling and play as liberatory practices to critique gender, race, and class. Henry explains, “My work is social commentary, but it’s process-driven. I found that I could use toys and dolls to tell stories, and I incorporated photography and craft to make sculpture. I now realize that I created my own medium. My work comments on what I observe, looking outward, and in turn, looks back at myself.”

After work, one evening, I was sitting on the dining room floor of Linda Bryant's apartment trying to do something with a couple of the action figures I was using. I remember laughing out loud at a scenario I cobbled together and David Hammons muttering, as he walked through the room, "How come she has so much fun making her stuff." I do and I like that I can surprise and amuse myself, so a good deal of what I latch onto is to see “What'll happen if…”

—Janet Olivia Henry

Install (19)

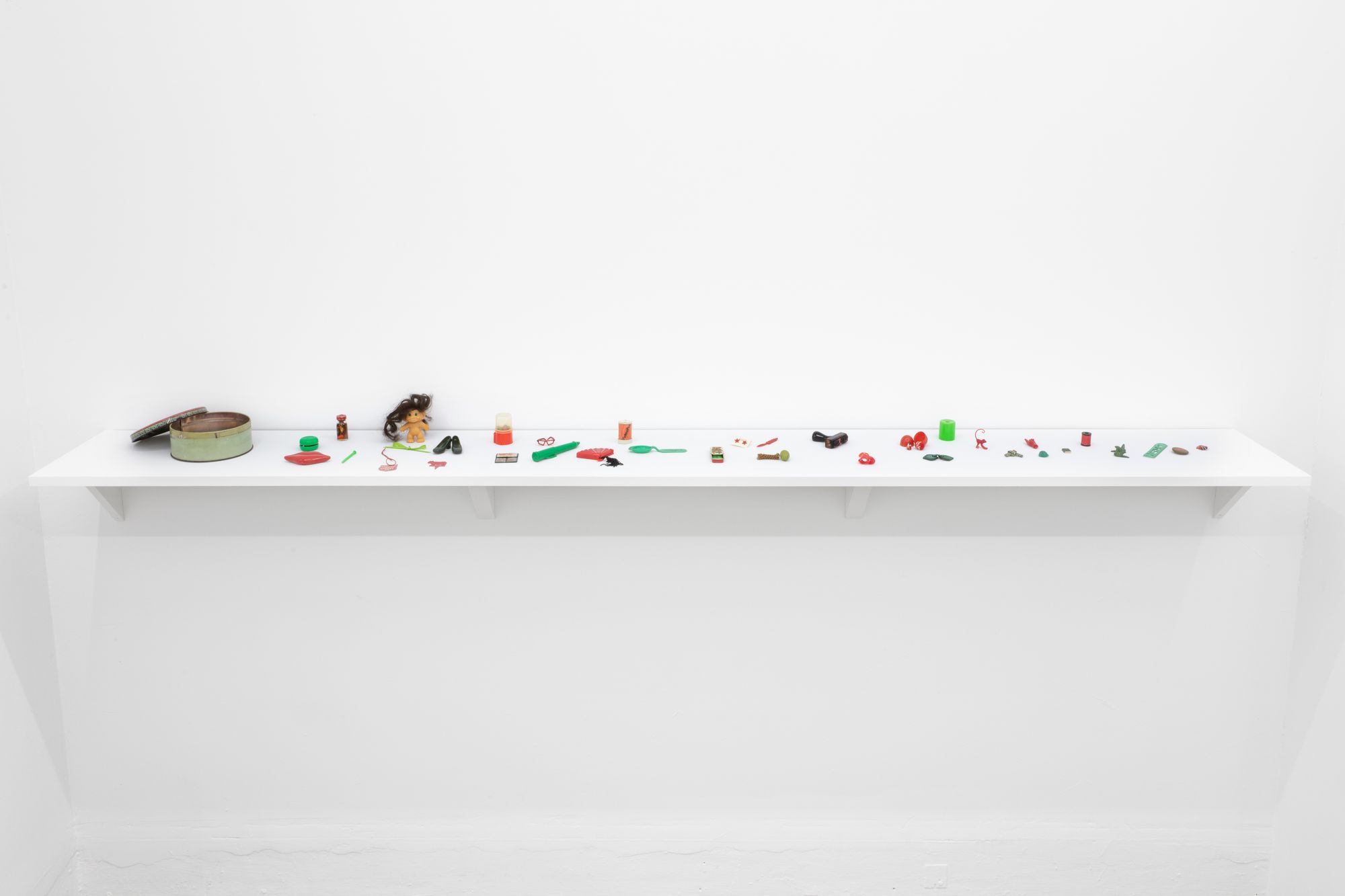

Juju Boxes

Juju Boxes are private, the kind of thing you can sit in a corner with and examine. Collectively these “art objects” create a story. Each item represents a word, a clump of things together makes a sentence. Once someone has one of these works, it’s more than ownership—it’s fluid and open—and people can bring their own ideas, experiences, and history to it. There are no rules on how they’re handled or displayed. You can’t help but conjure up associations and memories when handling the items in the boxes. —Janet Olivia Henry

Henry’s Juju Boxes are containers made with Japanese Washi paper boxes, baskets, clear vinyl bags, or cookie tins, which the artist carefully packed with miniatures, trinkets, and personal effects. Henry selected and grouped the objects according to a color scheme, theme, or to the specific person to whom the box is dedicated. The earliest of these sculptures, created in the early 1970s, were gifts for friends and included doll figurines and small objects. Henry recalls, “When I made them for other people, I picked things that I knew or thought they’d like."

The exhibition includes Juju Box for Myself (1976), a box dedicated to the artist’s mother, which has been installed on a long shelf, and Juju Box (Back from Antigua) (c.1976), which is displayed on a pedestal and features small bows from childhood shoes Henry wore on her return from a stay with family in Antigua.

The Juju Boxes are inspired by Henry’s life-long engagement with collecting miniatures and dolls, and her relationship to Juju—an African and Afro-diasporic spiritual tradition in which objects are associated with magical powers. The word “juju” is thought to be derived from the French word joujou (“plaything”), and Henry’s interest in toys lies in their potential for storytelling. She explains, “My work, it’s social commentary. What I found is that American culture had been replicated in miniature” and “with the Juju boxes, anyone could create their own magic—whatever paradise or fantasy a person desires.”

The majority of Henry’s Juju Boxes were gifted to friends or sold in the gift shop at Jamaica Center for Arts and Learning during the 1970s and are now lost. Others were disassembled by the artist and incorporated into different artworks. As Henry notes, “I realized that the dolls and their clothing and accessories could be used separately to tell stories.” These include her seminal work Juju Bag for a White Protestant Male (WPM) (1979–80)—displayed here hanging from a hook on the wall of the gallery—and the iconic dioramas Henry made in the early 1980s, two of which were recently on view at The Museum of Modern Art, New York, as part of the exhibition Just Above Midtown: Changing Spaces (2022).

Juju Bag for a White Protestant Male (WPM)

Expanding on the materials and ideas of the Juju Boxes, Henry created Juju Bag for a White Protestant Male (WPM) in 1979–80 by assembling found and altered dolls, miniatures, and her own creative writing to develop fictional characters and narratives. Like the Juju Boxes, the Juju Bag is open to various modes of engagement and display.

Juju Bag for a White Protestant Male (WPM) comprises a transparent tote bag sewn from clear vinyl and stuffed with eight small vinyl sleeves, each filled with a selection of dolls, miniature accouterments, and narrative texts. One such vinyl sleeve features a Black doll, miniatures (including a baseball bat, Nivea lotion, and a blonde wig), and a paper card with a description that reads: “Here we have ‘Little Cullid Kid’ aka Mercury Johnson… White Protestant Male (WPM)’s best friend from prep school (or any company sponsored rehabilitation project), especially when wearing the blonde wig).” Using the logic of satire, humor, and play, Henry creates a taxonomy of social relations, stereotypes, and critique.

Christian Cullid Lady, Neggerotti Melodrama, What's in the Moat Ain't No Different from They's What's in the Castle, White Protestant Male (WPM)

During Henry’s residency at The Studio Museum in Harlem (1983) and her years working at Just Above Midtown (JAM) in the late ’70s and early ’80s (she participated as an artist-member, graphic designer, and administrative assistant), Henry developed elaborate narratives using varied strategies such as photography, sculpture, and creative writing. White Protestant Male developed directly out of the artist’s Juju Boxes and was the first of the stories she imagined with toys and photography. Subsequent narratives, which Henry calls “examinations of archetypes,” include Christian Cullid Lady, Neggerotti Melodrama, and What's in the Moat Ain't No Different from They's What's in the Castle.

Henry set up a makeshift studio in the basement of JAM with a table, clamp lights, a black garbage bag, and a camera, and photographed tableaux that staged her collection of toys. She frequently altered the dolls’ hair, makeup, and clothing to reimagine them as characters in her own stories: a plastic doll of Lieutenant Uhura, the first African American character on Star Trek, was recast as Henry having a morning coffee in her home garden; a doll of the young daughter on the television show The Waltons was transformed into Mrs. Protestant White Male; Billie “Buckwheat” Thomas from Our Gang was reimagined as a friend of Mr. and Mrs. Protestant White Male; and a figurine of the wizard from The Wizard of Oz was recast as art dealer and gallerist Ivan Karp. Alongside her dioramas and photographs, Henry also wrote stories and dialogue for the characters, which she methodically cataloged in binders.

Lariats

In 1983, Henry made the first of her Lariat soft sculptures using prints of her photographs of the dolls and their accouterments. Each of the works is an assemblage of these color copier enlargements and excerpts of the artist’s writing printed on paper, which she sewed into clear vinyl and stuffed with batting (Poly-Fil, shredded US currency, and metallic cellophane). These elements are strung together on lengths of knotted cord, metal chain, and telephone wire, and are punctuated with clusters of charms and colorful beads. The sculptures are portraits of the characters in Henry’s narratives—among them White Protestant Male, Christian Cullid Lady’s son (Prince Nathaniel), and Denise from Them What's in the Moat Ain't No Different from They's What's in the Castle.

These image-objects expand the potential for storytelling across multiple registers and evoke a wide range of associations: quilted dolls, charm bracelets, comic book speech bubbles, fragmented bodies, and talismans. Henry explains, “A lariat is an open-ended necklace. My Lariat sculptures are malleable—they take on a new shape every time they're handled or displayed. Each one has a narrative. Some of the written passages are presented like an exhibition label, others are sewn into vinyl, batted, and interwoven within the piece.”

TWOS

TWOS is an ongoing project in which Henry explores the visual dynamic of two connected but ostensibly disparate visual elements. As she explains, “I wanted to see what the effect would be if I combined two completely different visual elements in one piece. They clash, meld, and bleed into each other. I found over fifty ways of saying ‘two’ and set about making and titling a piece for each of the words. The TWOS are an idea that started percolating in the early ’90s, when I taught art at the Lower Lab School and was thinking about creating objects that represent symbols of authority.”

Henry’s TWOS evolved out of her voracious activity of collecting beads—both commercial and handmade—her practice of making jewelry, and her fascination with undersea creatures and habitats, complemented by her interest in the forms and techniques she discovered in Hideyuki Oka’s book How to Wrap Five Eggs: Traditional Japanese Packaging (1975). Like many of Henry’s works, the TWOS can be installed and configured in any number of ways including hanging in the round or on the wall.

Henry builds each of the sculptures on two spines of waxed thread that she wraps and braids. One of the lengths supports hundreds of beads and charms that Henry knots, one at a time, into clusters of variegated color and texture. Beyond their visual hybridity, the beads and charms suggest a wide array of cultural networks of association and exchange, among them Czechoslovakian marriage beads traded in Mali; Chinese sitting cat carved bone beads; painted pink metal-cast flowers from the United Kingdom; Brazilian sliced Tagua nut seeds; Ethiopian brass bicone beads; Guinean phenol-formaldehyde (African amber); Tibetan silver whale tail charms; Cuban rosary pea seed beads; red-dyed Mexican howlite; 1950s hair curlers from a pink bubble bath charm set; and antique Venetian glass disks.

On the second braided spine, Henry assembles finger-like objects created with lines of dialogue she wrote for the characters she developed with her dolls beginning in the late 1970s. Henry prints the text on paper and sews it into vinyl, which she quilts with Poly-Fil batting. These segments of concrete text are threaded on the spine and interspersed with beads and charms to create a voluminous array of dialogue—a narrative that unfolds like individual speech bubbles in a comic or text chain. These stories satirize gender, race, and class and collide with the clusters of beads and charms, themselves endowed with their histories as objects of symbolic and spiritual value, as means of currency and exchange, and as emblems of power relationships between cultures and nations.

Crystal Casita

Henry’s Crystal Casita (2024) is the most recent of her ongoing diorama constructions, which she began in the late ’70s. The Casita depicts an idealized version of Henry’s studio, with the walls and floor constructed out of Lego-like building blocks which the artist refers to as IPBs (Interlocking Plastic Bricks). Henry first employed IPBs in 1993 to create a medieval walled town, which evolved into an ambitious architectural sculpture, NYC Phantasmagoria. The sprawling model of urban space is an ongoing project—currently more than twelve feet long—and stands as a pastiche of architecture, parks, and infrastructure inspired by New York, Rio de Janeiro, and other international cities.

The Crystal Casita’s most prominent architectural feature is its walls, which Henry constructed with translucent IPBs that resemble glass bricks, their “crystal” quality infusing the studio with light. The silhouette of a figure is visible from outside the diorama, while the studio walls refract and emanate light. The interior has a modern feel, its pristine white floor patterned with a mosaic of interlocking geometric tiles. A Black doll, which Henry modified into a representation of herself—she cut and styled the hair, changed the clothing, added glasses, and rubbed off the makeup—sits at a folding table. The setting is sparse: the walls are bare, a miniature tote bag and pair of sneakers rest casually on the floor, and three diminutive items are arranged on the table (a plastic container of sliced watermelon, a canned beverage, and a box of Chinese pastries) in front of the doll. Nearby, a cart of clip lights and a stack of toy motorcycles that stand in for a generic found-object sculpture suggest art production. Henry appears at rest—her shoes are off, she has snacks at hand, and she is bathed in diffused light. The studio is a place of serenity, contemplation, and creative reverie.

The Crystal Casita on view at Gordon Robichaux is the first in a series of twelve dioramas in which Henry will foreground women’s creative practices, specifically those of her peers in the Southeast Queens Artist Association. Henry plans to build eleven of the casita dioramas and invite fellow artists in the association to create their own self-portraits by representing their likenesses, artworks, and studios with dolls and miniatures. The project is in keeping with Henry’s six-decade-long commitment to collectivity, community, and activism in her work as an educator; an artist-member, designer, and assistant at JAM; a force in shepherding community mural projects with children and young adults; and a leader of collaborative drum groups at the Women's Action Coalition (WAC) and Project EATS.

Works

Mrs White Protestant Male (WPM)

Color copies, vinyl, paper, assorted beads, shredded currency, shredded paper, shredded cellophane, Poly-Fil, cotton thread, braided and wrapped waxed nylon thread

76 x 20 x 17 inches

1994

Neggerotti Melodrama (Claude)

Color copies, vinyl, paper, assorted beads, shredded currency, shredded cellophane, Poly-Fil, thread, braided and wrapped waxed nylon thread

18 x 11 x 4.5 inches

c. 1983

Christian Cullid Lady's Son (Prince Nathaniel)

Color copies, vinyl, paper, assorted beads, shredded paper, Poly-Fil, cotton thread, braided and wrapped waxed nylon thread

10 x 6.5 x 3.25 inches

1983

Christian Cullid Lady's Daughter

Color copies, vinyl, paper, assorted beads, shredded paper, Poly-Fil, cotton thread, braided and wrapped waxed nylon thread

20 x 6 x 3.75 inches

1983

White Protestant Male (WPM)

Color copies, vinyl, paper, assorted beads, shredded currency, shredded paper, shredded cellophane, Poly-Fil, cotton thread, braided and wrapped waxed nylon thread

26 x 64 x 4.25 inches

1983

Neggerotti Melodrama (Denise)

Color copies, vinyl, paper, assorted beads, cotton thread, braided and wrapped waxed nylon thread

12 x 9 x 2.5 inches