Past

A Page from My Intimate Journal (Part I) —

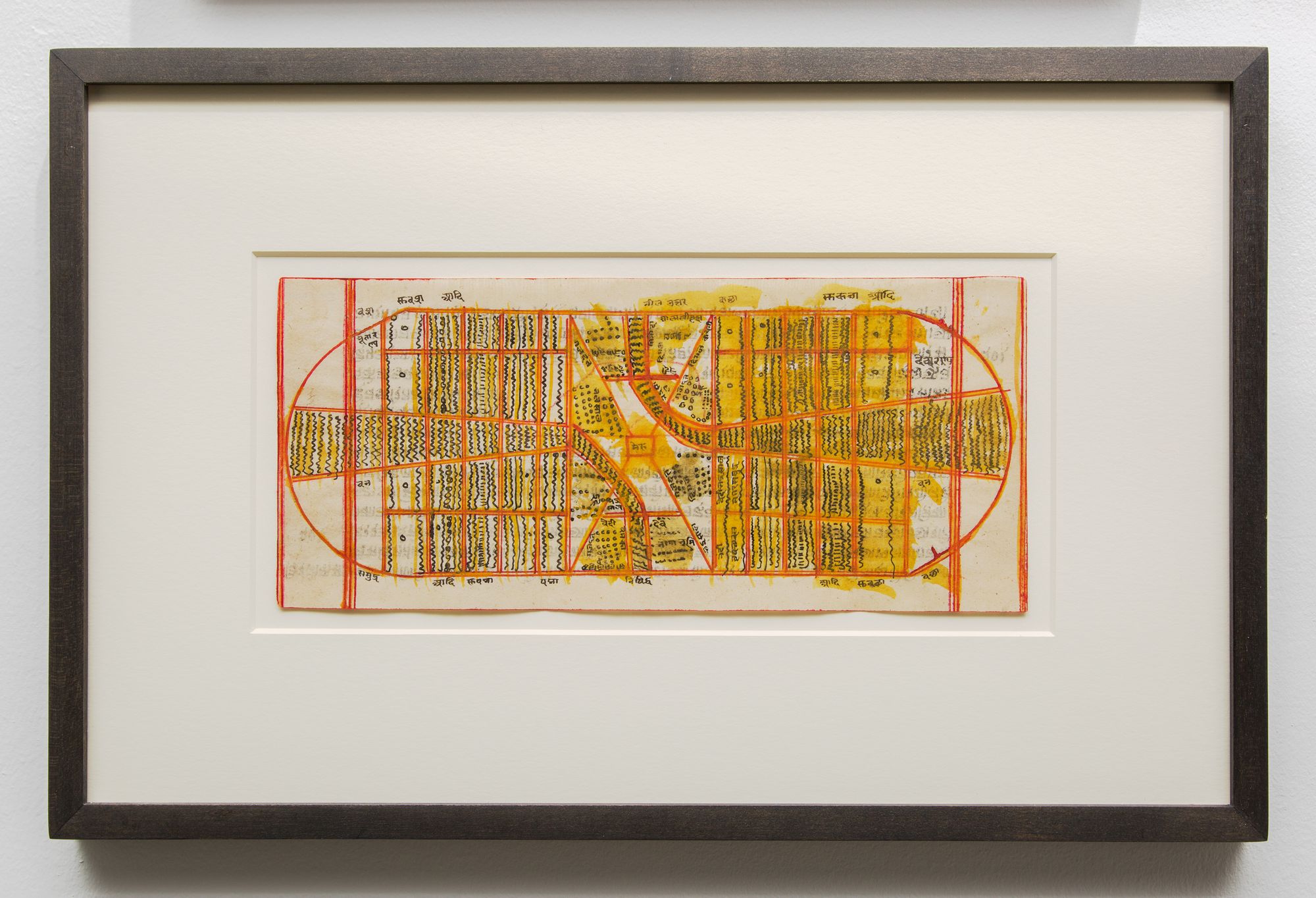

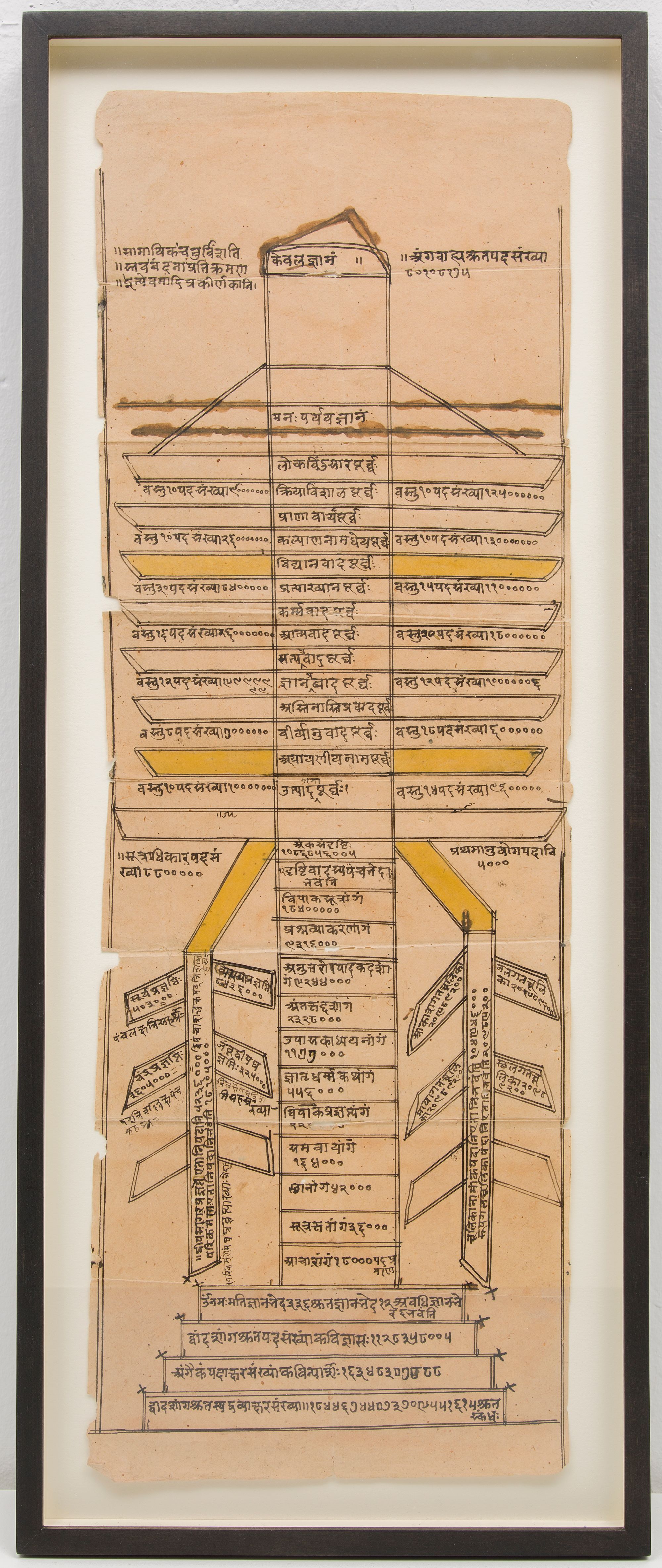

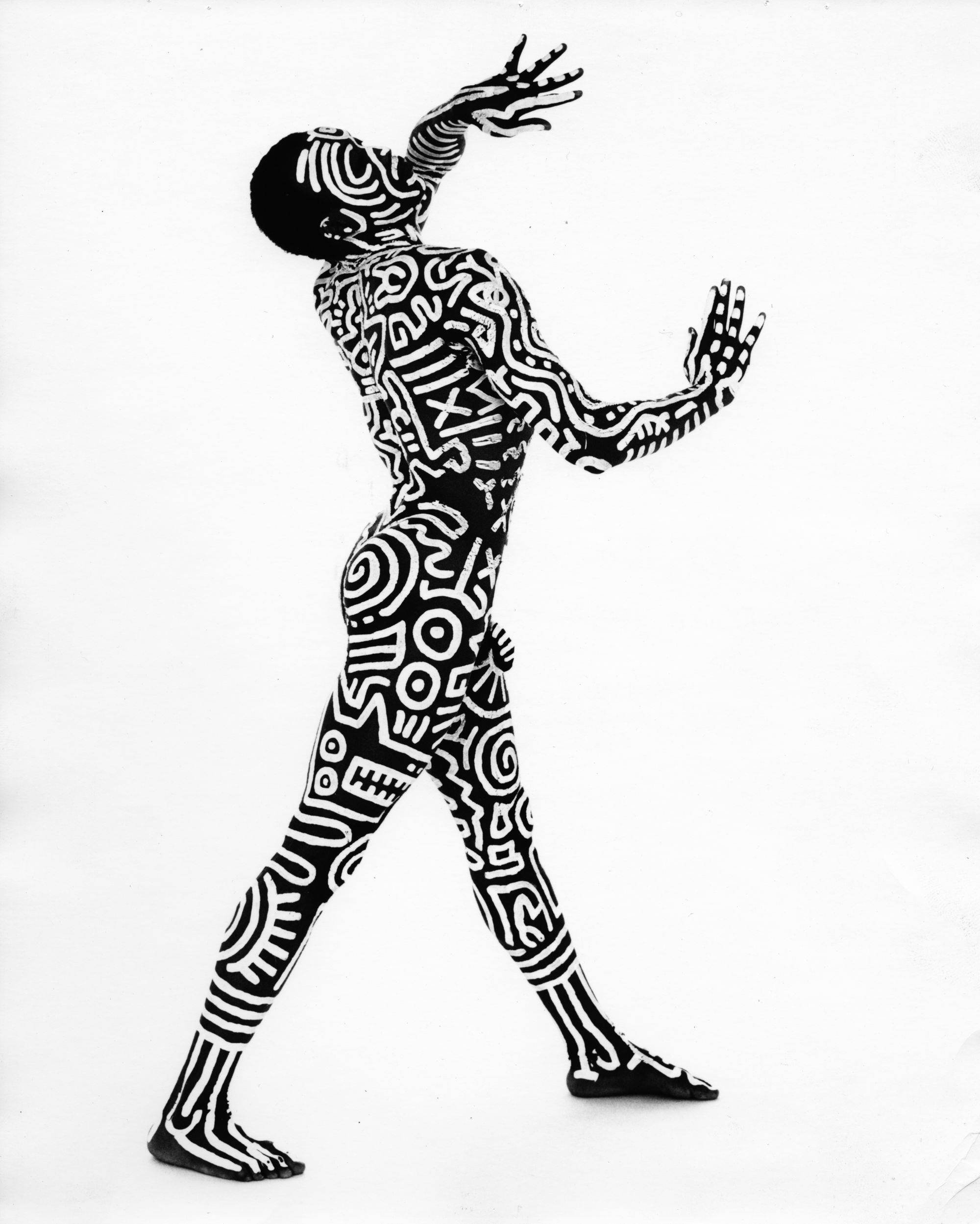

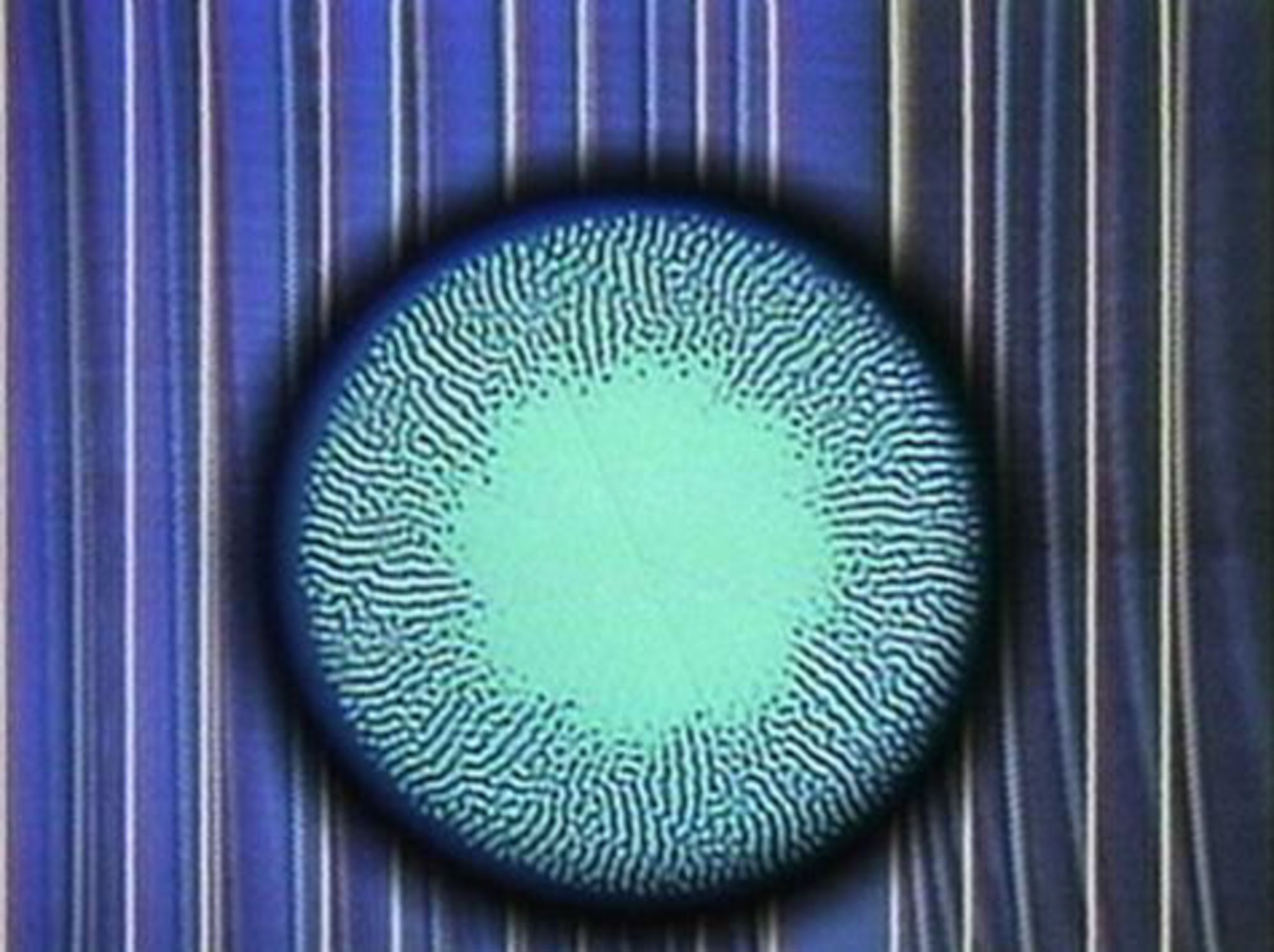

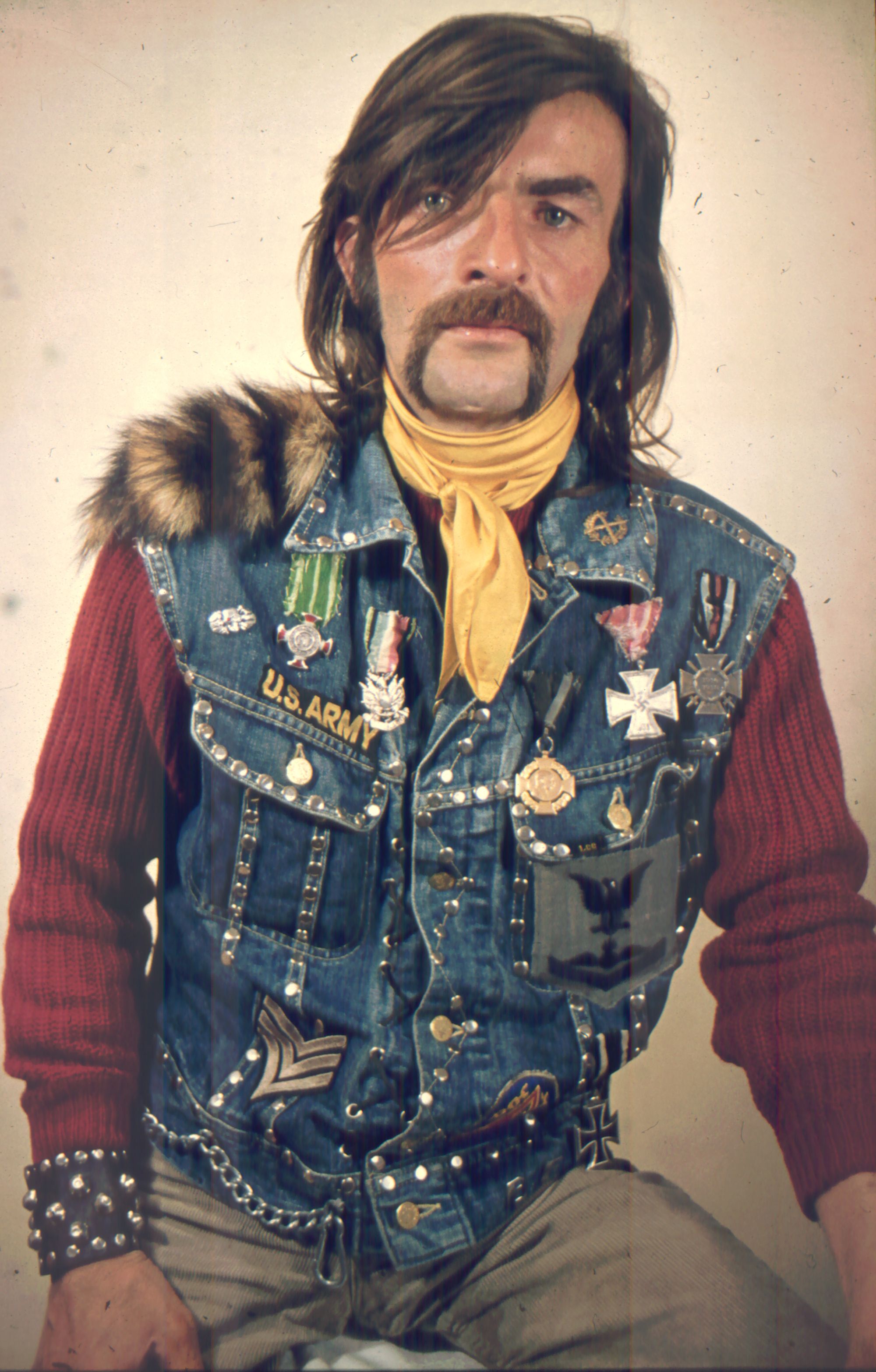

Wayne Koestenbaum, Frederick Weston, Otis Houston Jr., Jenni Crain, Matt Connors, Florence Derive, Miles Huston, Siobhan Liddell, Sanou Oumar, Matt Paweski, Schorr Collier, Kerry Schuss, Martin Wong, Elisabeth Kley, Math Bass, Hawkins Bolden, Guy de Cointet, Lucky DeBellevue, Liz Deschenes, Shannon Ebner, Melvin Edwards, Vincent Fecteau, Denzil Forrester, Barbara Hammer, James Hoff, Marc Hundley, Shirley Jaffe, Caitlin Keogh, Shigeko Kubota, Magic Markings Anonymous, Darinka Novitovic, Bernard Piffaretti, Howardena Pindell, Charlotte Posenenske, Michael Queenland, Stuart Sherman, Amy Sillman, Alison Smith, Gwen Smith, Martine Syms, Tseng Kwong Chi, Stan Vanderbeek, Melvin Way, Karlheinz Weinberger, B. Wurtz, Amy Yao

Feb. 11–Apr. 8, 2018

New York

An exhibition comprised of an installation of works by forty-six artists, a commissioned fable by Wayne Koestenbaum, videos in cooperation with EAI (Electronic Arts Intermix), and two events. The exhibition is titled after a work by Guy de Cointet included within the installation.

Performances:

March 4: Wayne Koestenbaum, Darinka Novitovic, Frederick Weston

April 1: Amy Sillman, B. Wurtz, Amy Yao, Otis Houston Jr.

Math Bass, Hawkins Bolden, Jenni Crain, Guy de Cointet, Matt Connors, Lucky DeBellevue, Florence Derive, Liz Deschenes, Shannon Ebner, Melvin Edwards, Vincent Fecteau, Denzil Forrester, Barbara Hammer, James Hoff, Otis Houston Jr., Marc Hundley, Miles Huston, Shirley Jaffe, Caitlin Keogh, Elisabeth Kley, Wayne Koestenbaum, Shigeko Kubota, Siobhan Liddell, Magic Markings, Darinka Novitovic, Sanou Oumar, Matt Paweski, Bernard Piffaretti, Howardena Pindell, Charlotte Posenenske, Michael Queenland, Collier Schorr, Kerry Schuss, Stuart Sherman, Amy Sillman, Alison Smith, Gwen Smith, Martine Syms, Tseng Kwong Chi, Stan Vanderbeek, Melvin Way, Karlheinz Weinberger, Frederick Weston, Martin Wong, B. Wurtz, Amy Yao

Install (19)

A Page from My Intimate Journal — Part 1

A fable by Wayne Koestenbaum

Too many of us—the marked, the curiously emblazoned—were crowded together in one room. We would all dwell, for the duration, in a space advertised as ample, though it was in fact a cramped, low-ceilinged attic. Through its windows, we could see defunct factories ranged against the unnaturally orange sky; and we could hear, amid ambulance sirens, the shouts of miscreants, thronged on street corners for cabal and cheerleading. Squatters, grifters, and dubious political organizations now occupied the condemned factories. We attic-dwellers tried to feel superior to the factory-squatters, but we, too, faced squalid circumstances. Forced to sleep five to a bed, and to excrete in slop pots, we received few instructions from our boss: aside from scavenging food scraps, and generating heat from body contact, we were commanded to scrawl confessions and pleas in the 5 x 8-inch pads with which we were generously supplied, as if these modestly sized ledgers were a new style of zwieback biscuit.

Sexual misconduct, we knew upon arrival, would infect the attic, where the five-to-a-bed policy deprived us of privacy. As our first task of self-governance, we elected officers for adjudicating cases of sexual wrongdoing, judges who would eject any offenders from premises not luxurious but still preferable to dwelling in unheated factories or on the fume-engulfed streets. As our second task, which would consume the rest of our lives, we began constructing appropriate codes and signals for communicating our plight, and for broadcasting, to future generations, the nature of our five-to-a-bed culture; by carefully limning—in jagged codes—our situation, we might offer guidance to our descendants, should there still be an earth for these unlucky creatures to inhabit.

Our boss, a feared enigma named Rack Gretel, barked out new directions every fifteen minutes. Every quarter-hour it was time, Rack Gretel said, for us to concoct a new code. Fruitless were our attempts to explain to Rack Gretel that codes could be developed only slowly; hours, months, years, decades are required for codes to germinate, whether composed of fig leaf or of squirrel offal. Rack Gretel was a strange slab of human tendency, lacking the clearly defined features of a Popeye or a Pompidou. What Rack Gretel wanted we couldn’t discover; all we could discern, and grow to love, was the crude charisma of his tempo, his insistence that all code-creating activity take place at a fast clip.

An emissary—sacrificial, elegant—arose from our five-to-a-bed midst, a comely and ambiguous slip of a girlboy named Careful Last. Careful Last, whose clothing had managed to escape the soiling effects of our straitened circumstance, stepped forward—in a pants-dress, composed of towels, scarves, denim, plastic bags, leather, velvet, and heaps of what even in our pleasure-deprived endtime we still called “attitude”—and offered to carry intelligence of our difficulties to the ears of the factory dwellers, who were, we would soon learn, compelled by their ingenious warlords to invent codes and signals and to inscribe them on 5 x 8-inch pads identical to ours. Careful Last, who had been singled out as the “favorite”—the pampered catamite—of Rack Gretel, took the most refined and the least helpful of our jottings, bundled the pages into a khaki satchel, and took them through the underground tunnel linking our building to the principal factories across the bruising, cabal-haunted thoroughfare. The next day, Careful Last returned, carrying a satchel of factory-generated codes, to our overcrowded domicile.

And so, for months and months, the traffic continued, the daily exchange of codes and signals, from attic to factory, and back again, in the satchel of Careful Last, who became, by virtue of the lightheartedness with which he dispatched his responsibilities, a cult figure. And now, if it is permissible to speak in my own voice, and to express uncouth biases, please let me admit that the fine points of Careful Last’s deportment are my primary passion. The pleasure of keeping close watch over Careful’s behavior is the only reason I haven’t swallowed poison, in these difficult months of parched subsistence and forced code production.

The same five people do not sleep every night in the same bed; we rotate, according to a system whose niceties and incoherences are managed by Rack Gretel.

One night, in late January, after the snow had fallen for hours, a blizzard tinted amber by the polluted light through which the flakes traveled, I managed, due to a lapse in Rack Gretel’s accounting system (he had fallen asleep over a glass of piney bitters, and I had tampered with his ledger-book), to land a place within Careful Last’s bed. Just a moment earlier, Careful Last had returned from the nightly journey through the underground tunnel from factories whose complexities and odiferous horrors I could hardly imagine, and back to an attic that seemed, in comparison, a petit-bourgeois paradise. Beneath the burlap blanket I lay, with three other unnamed, uncared-for code developers; I could feel Careful Last’s slender body slip under the burlap beside me, and so, with a gentleness I feared was criminal, I slithered my body against Careful’s. I pressed without genital specificity; neither my genitals, nor Careful’s, whatever their nature and composition, had any part in this travelogue. What obtained, between Careful and me, in those last apocalyptic hours, formed a new code we would not in the morning have the temerity or skill to commit to paper, though I can, here, through the medium of oral communication, through groan and whisper and vocal persiflage, tell you a few signal features of our congress.

Careful performed some action on Careful’s own body; I witnessed the action, but I did not understand it. I, in response, or in imitation, performed what I hoped was a similar action upon my own body, which was superficially thicker than Careful’s body but equally confusing in its characteristics. Careful, however, made no sign to indicate awareness that I was present in the same bed or that I was engaged in a parallel set of enigmatic, graphic, culpable motions, with a robustness almost agricultural. To Careful, I adhered, in my sticky fashion; the stickiness, not a bodily emission, came from my earnestness, as well as from the physical conditions—grease, dust, and other, unsymbolizable forms of particulate dirt—that filled the attic. This impious grime allowed my body to glue itself, with a passé fondness, to incognizant Careful.

Then a cruel thing happened, and the cruelty was Careful’s. Careful enforced a separation, with skills I cannot comprehend, from my resinous body, and pressed closer to another unnamed, unseen personage in our bed. No longer were my limbs and loins receiving Careful’s nectar. A sound, wet and soughing, filled the bed; if you have ever heard a refrigerator moaning, when its useful life is almost at an end, then you will understand the noise that Careful made, and how that noise inspired in me a wish to kill Careful. The malevolence arose in me, and I nursed it; but the intent could not communicate itself to my hands. My hands had grown heavy and numb. I tried to wiggle my fingers; they responded only sluggishly. To my hands I bade farewell. This adieu I felt strongly, but I could not communicate it to my body. Whatever system of code-sharing that formerly tied my organism together seemed to have collapsed.

At that moment, Careful turned around and clasped me. Careful kissed me, and though my mouth had no desire to open, I could feel it become a vacancy available to admit Careful’s tongue. Careful’s tongue, however, was a joke tongue, not quite coterminous with Careful’s actual opinions. Careful’s tongue attacked me with a spurious directness, a facticity, that declared itself not-quite-tongue. I therefore had no right to interpret Careful’s tongue as a sign of love. The tongue was a taunt. The tongue, though seeming to reward me, to anoint me anew with full-bodied life, and to restore communication between my wishes and my limbs, instead performed a severing. The tongue (if you will forgive my scientism) completed the divorce between cognition and organism.

Careful whispered in my ear, “I deplore what you have done to our system.”

“What system?” I whispered in cautious reply.

An unvoiced laugh caused Careful’s svelte body to shiver, like a doormat shaken out.

“The system you pretend to uphold, my dear idiot,” said Careful.

Careful’s candor, and its courtly expression, aroused in me a spasm of religious feeling.

“Could I accompany you tomorrow evening on your mission to the factories?” I asked, as I pressed my body against Careful’s.

Toward our bed, Rack Gretel stumbled with a hammer. Bang bang went the hammer on the bed’s steel rim. Cries arose from every denizen of the attic. Rack Gretel persevered in hammering the bed’s rim, with a rhythmic force that reminded me of a brutal passage from Carmina Burana, which I had sung in middle school, as a foreign exchange student in a country formerly celebrated for its mathematical and jurisprudential prowess but now mired in baroque webs of corruption.

Wearily, Careful rose. Careful had received the unmistakable summons. Only to Careful did the summons—the hammering blows—refer. The hammer’s retort signified Careful, as the logicians would formerly have said, in the highly literate country where I had the honor to be a foreign exchange student, although I was later expelled from school and sent back to my own country because of an infraction I’d committed with the school’s dean. The dean condemned me, though we had been involved together in this carnal misdeed, whose source, as always, lay in the soft areas concealed by belts and sashes.

For the rest of the night, only four people occupied the bed where recently Careful and I had undergone our peculiar procedure. I don’t want to stop telling you the story of Careful and me, of Careful and our civilization, of Careful and the ogre Rack, of the warehouses and the orange sky and the sweaty beds. I don’t want to stop inscribing codes in the 5 x 8-inch pads. I don’t want Careful to be punished. I want Careful to keep undertaking the perilous journey through the tunnel, nightly, to circulate intelligence of the codes and signals our two populations are heretically inscribing in our allotted pads. Always, at the end of a story, the story shuts itself down, as if the story were punishing itself for being a story, as if the codes were killing themselves because it was criminal to be a code.

The next morning, Rack served me a bowl of porridge. I hadn’t tasted porridge since my internment began. Kindness toward me, a kindness exercised by Rack, could only mean that Careful had been destroyed. A new softness, a new unctuousness and solicitude on Rack’s part, meant that Careful’s gracile, malarial ambiguities had been banished—whatever mortal injury a Rack-style banishment entailed. “Stop belly-aching about Careful,” you might say. “Didn’t you want to kill Careful, a few hours ago?” And so continues the cruel march of chronology, of logos, as my old nurse used to whimper, before shipping me off to the penal farm. “There goes logos,” Nurse would say, his whiskers brushing against my too-logical forehead. Before I left Nurse’s care, we together manufactured an ointment, vaguely medicinal. We developed a brochure to advertise the salubrious effects of our greasy concoction, and we sold the ointment to gullible travelers who frequented our hamlet, buried in a region far from the most popular rivers but near a lagoon crowded in all seasons with festive houseboats, some of them functioning not only as vacation properties but as haute-bourgeois restaurants. Nurse and I had the wit to escape responsibility for the atrocities that might have ensued from a too sanguine or too literal application of the ointment we sloppily produced.

The sound of a siren, outside the attic, splits open the atmosphere. I look down from the attic window and see the factories consumed by flames. Good night to codes and signals, to Careful and Rack. Good night to the rivalry between factories and attic. Good night to recollections of ointments purchased by houseboat visitors in the golden age before my multiple, unspecified expulsions. I am not immune to the disasters I describe. Purge that sentimental observation from the official record.

Works

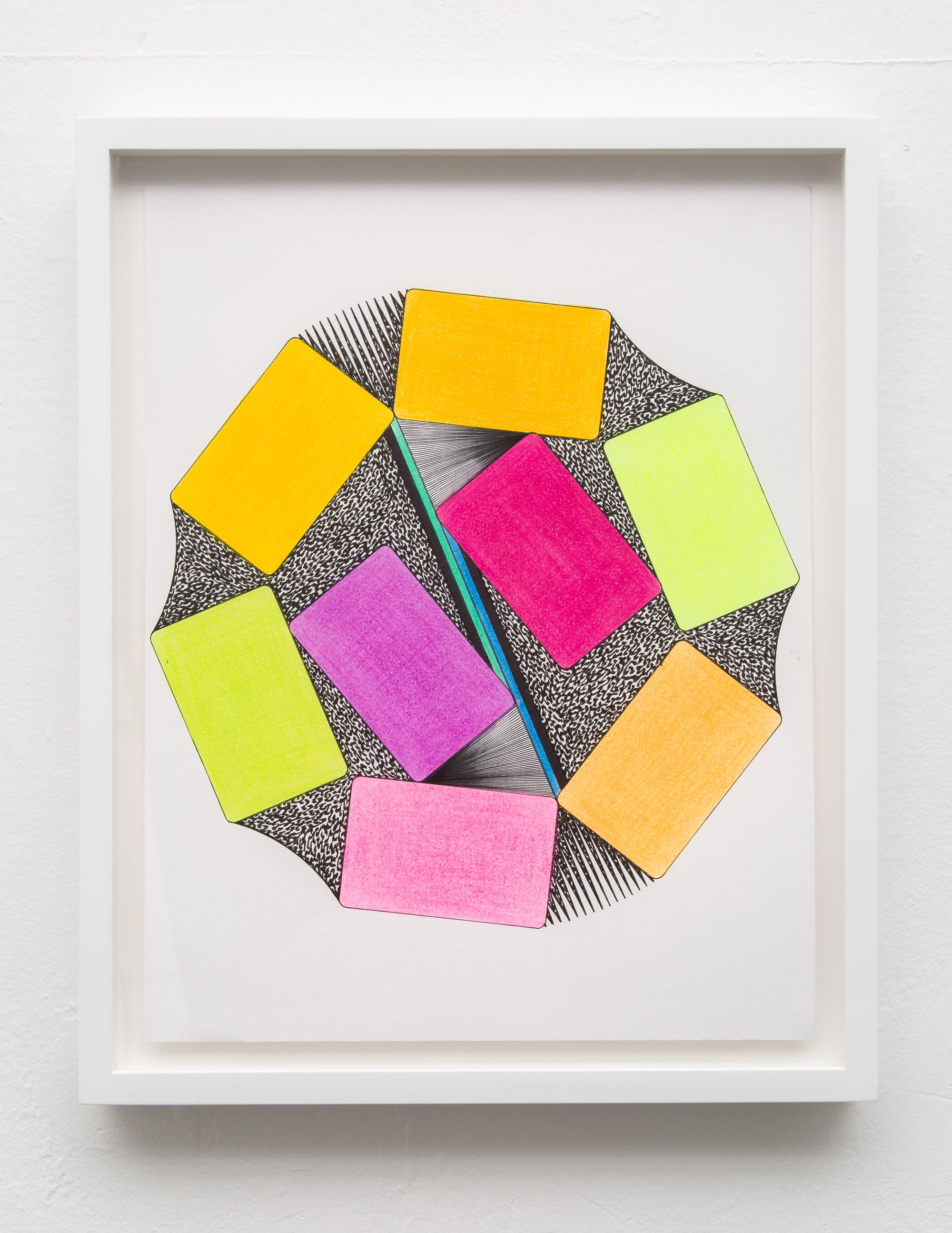

Math Bass, NEWZ!

Math Bass, NEWZ!

Gouache on canvas

40 x 42 inches

2017

Math Bass, Yellow Gate

Math Bass, Yellow Gate

Powder-coated steel

25.5 x 41 x 79 inches

2014

Hawkins Bolden, Untitled (scarecrow)

Hawkins Bolden, Untitled (scarecrow)

Mixed media assemblage

28 x 28 x 10 inches

c. 1980s

Hawkins Bolden, Untitled (scarecrow)

Hawkins Bolden, Untitled (scarecrow)

Mixed media assemblage

75 x 18 x 13.5 inches

c. 1980s

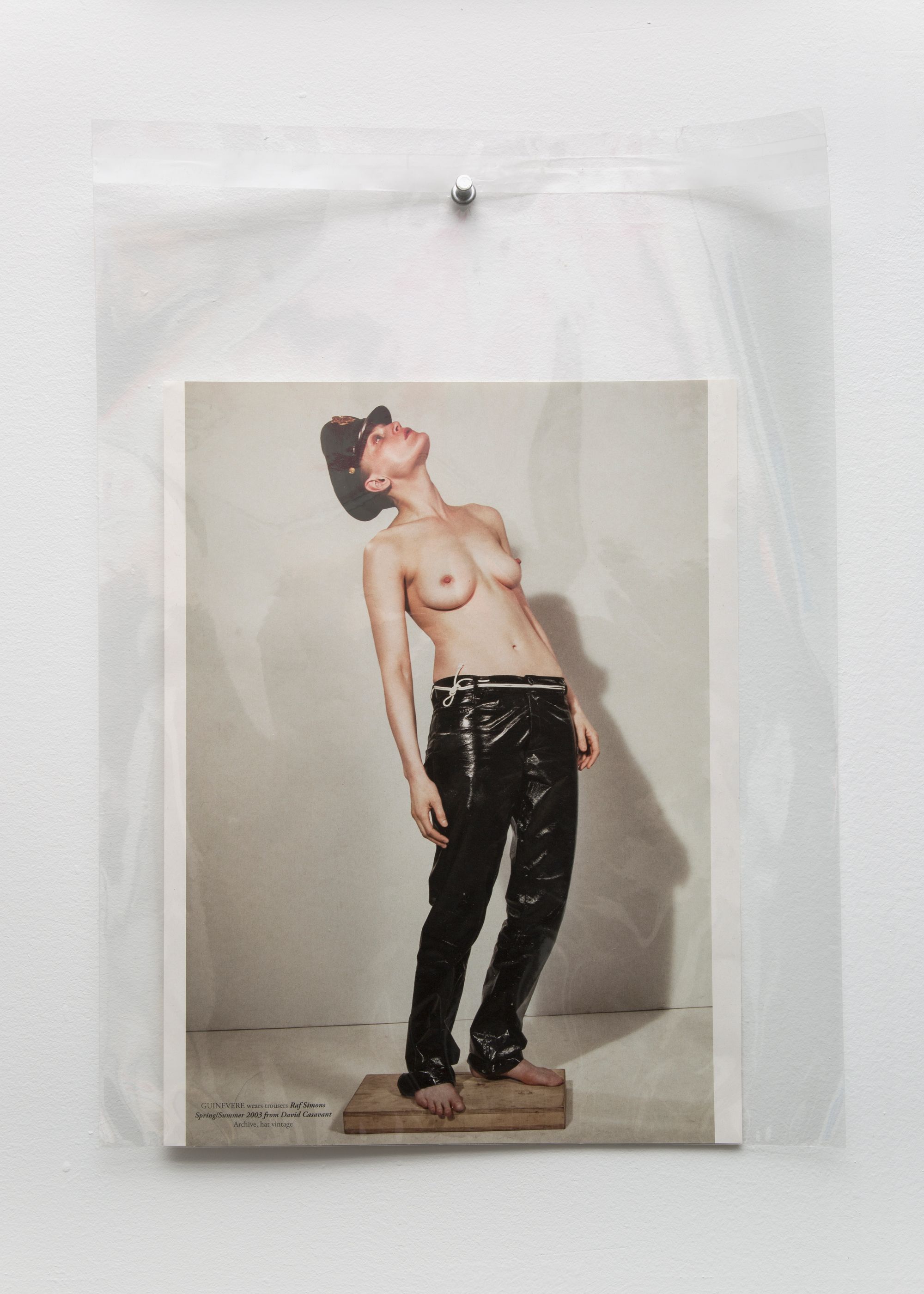

Jenni Crain, Untitled (4)

Jenni Crain, Untitled (4)

Baltic birch plywood, cotton canvas, and bass wood

9.13 x 81.5 x 34 inches

2018

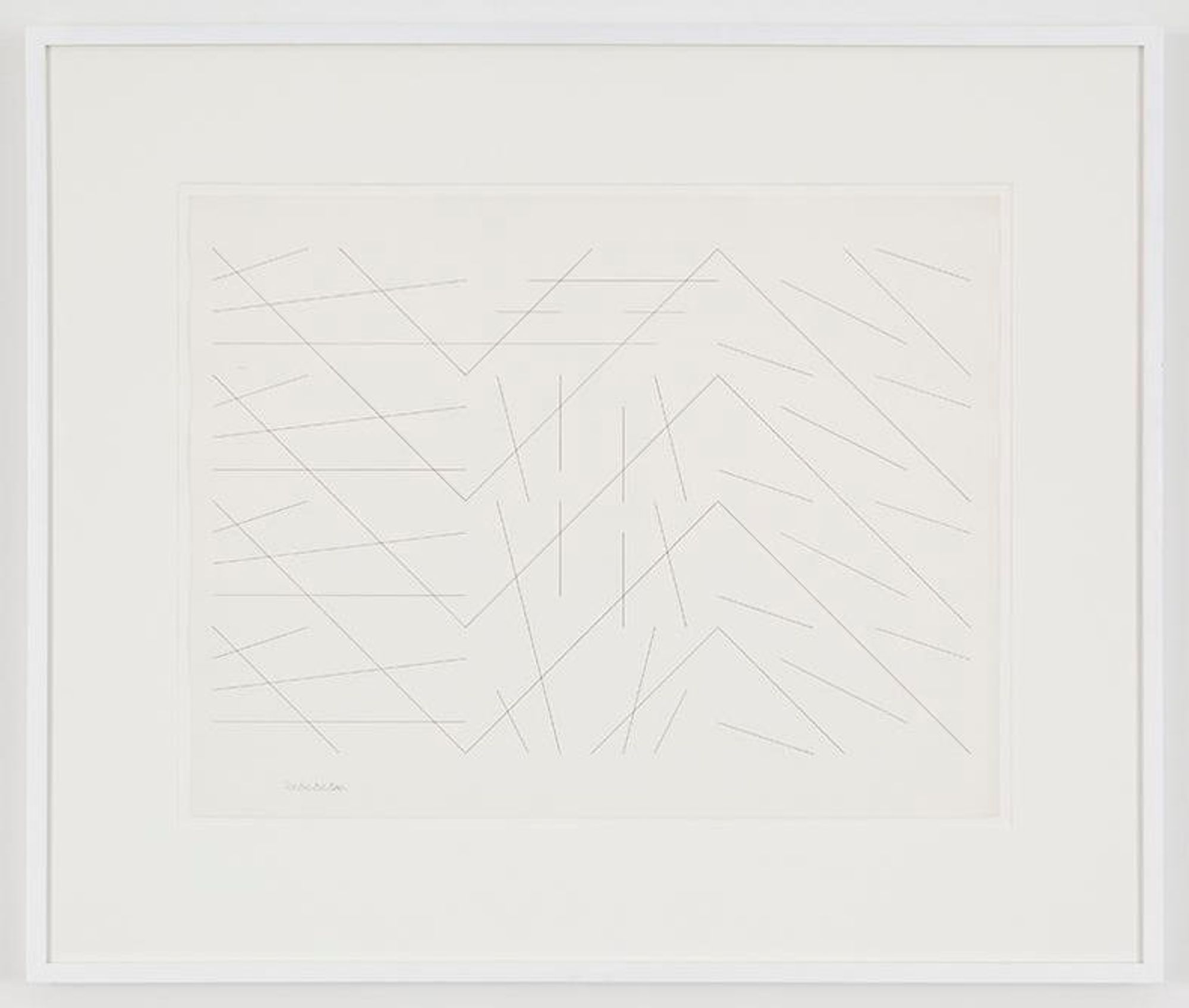

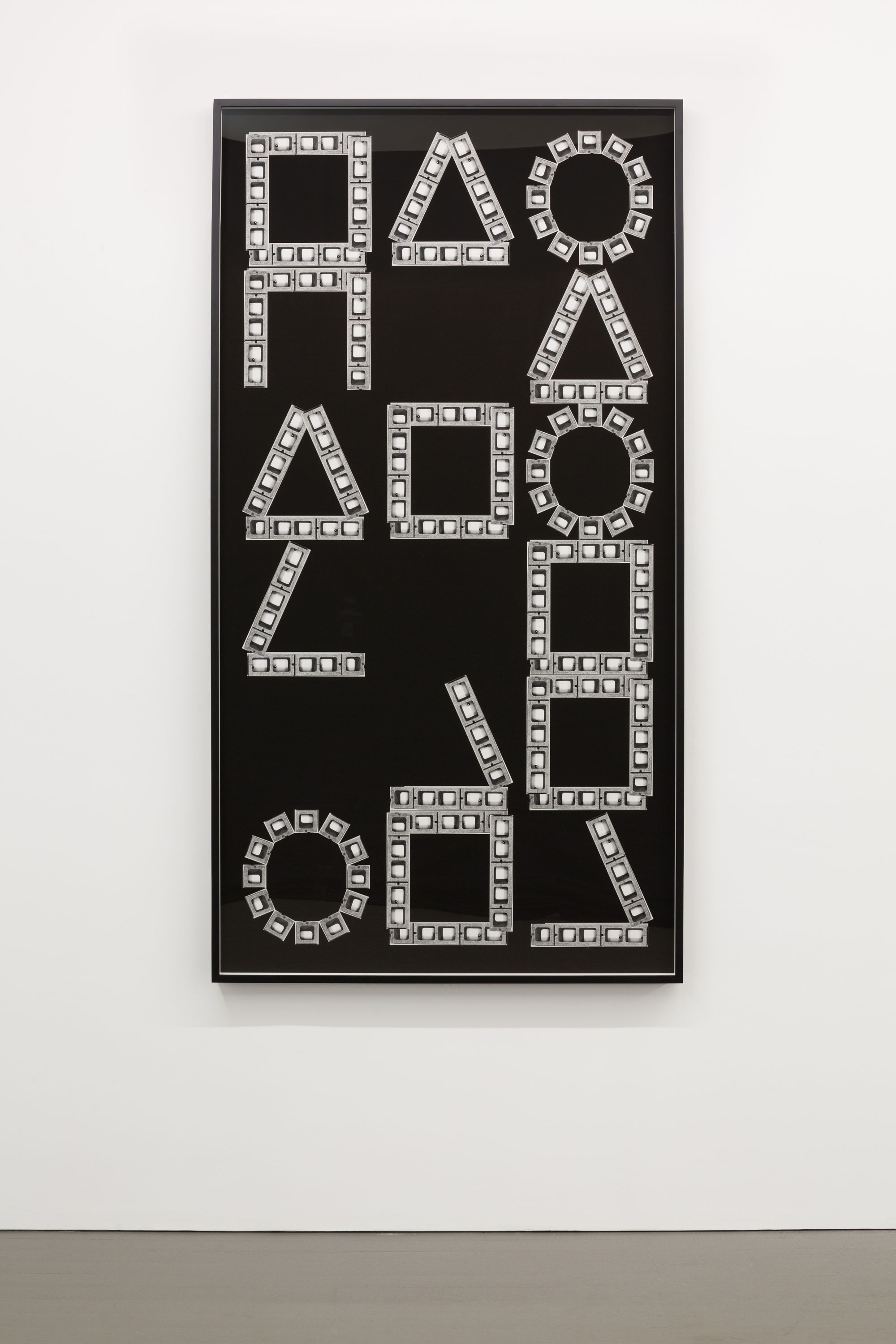

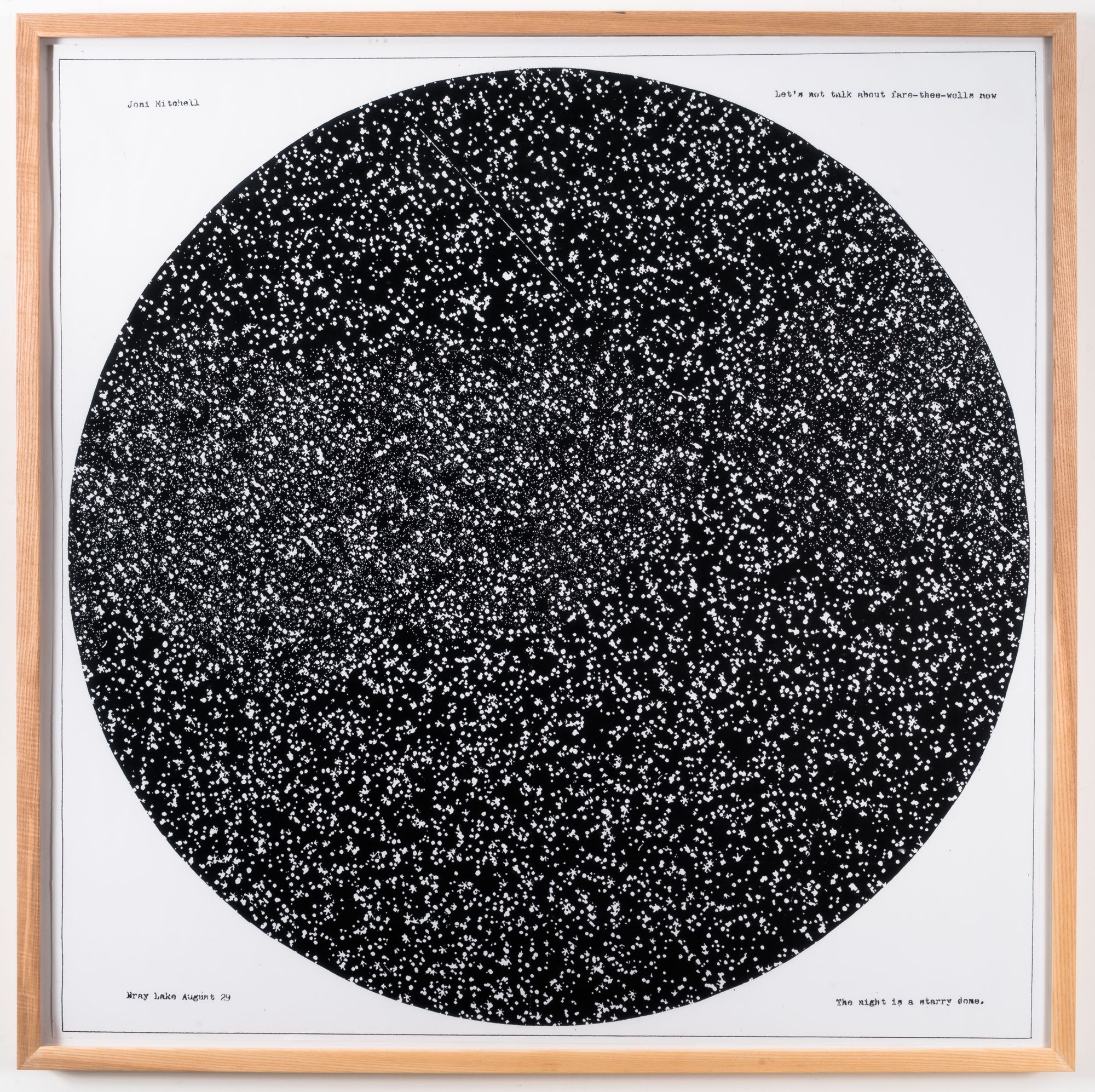

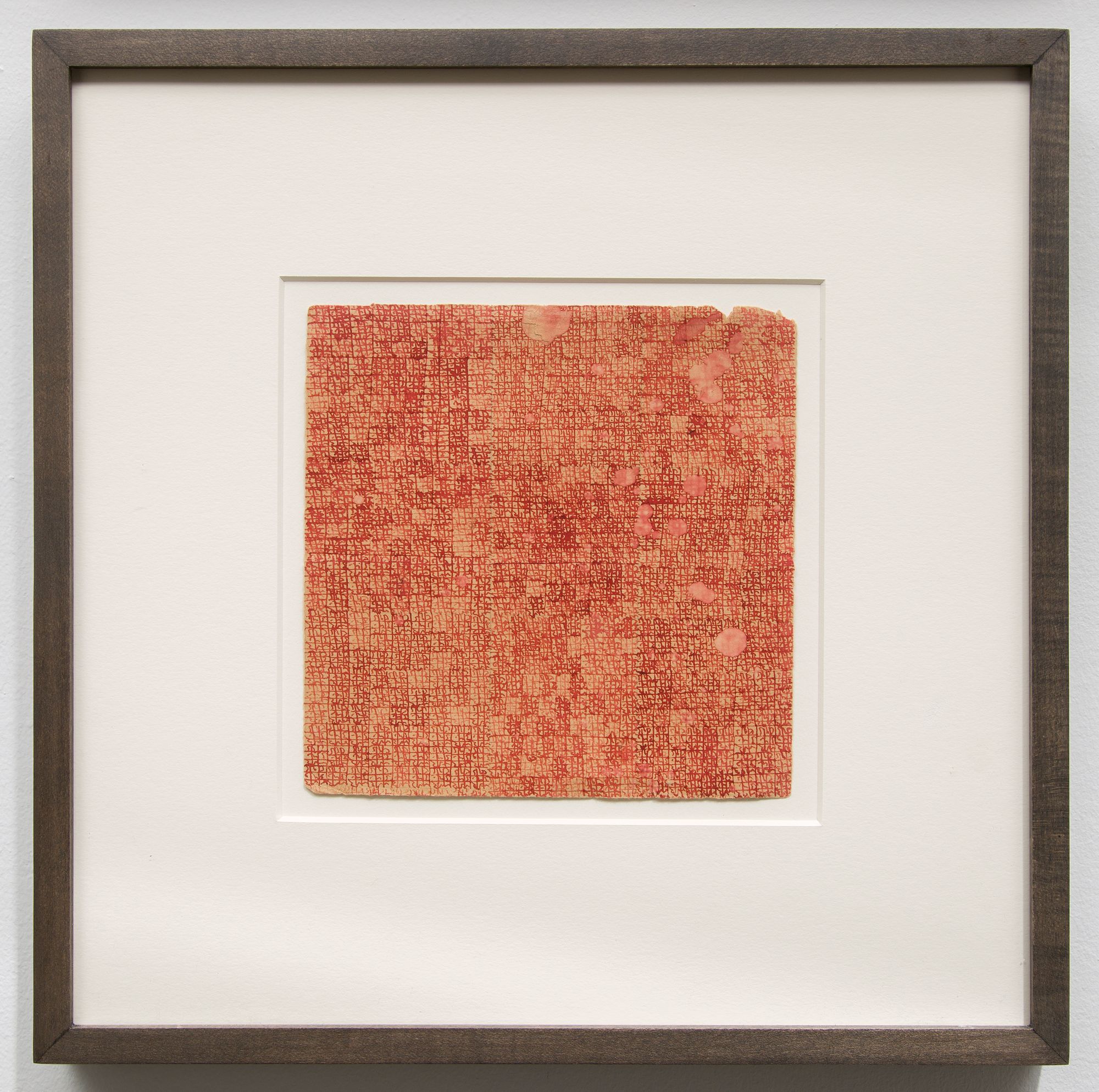

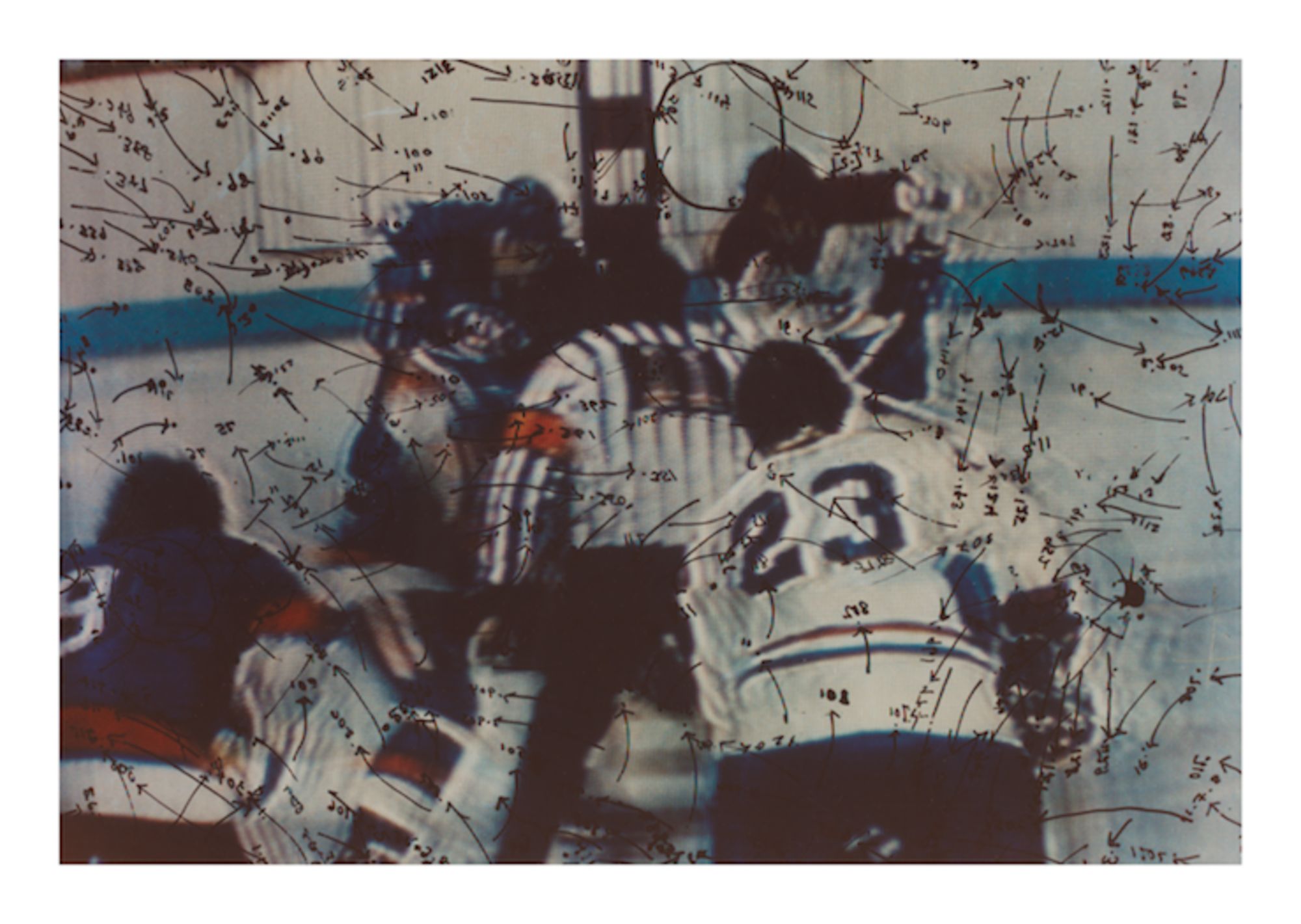

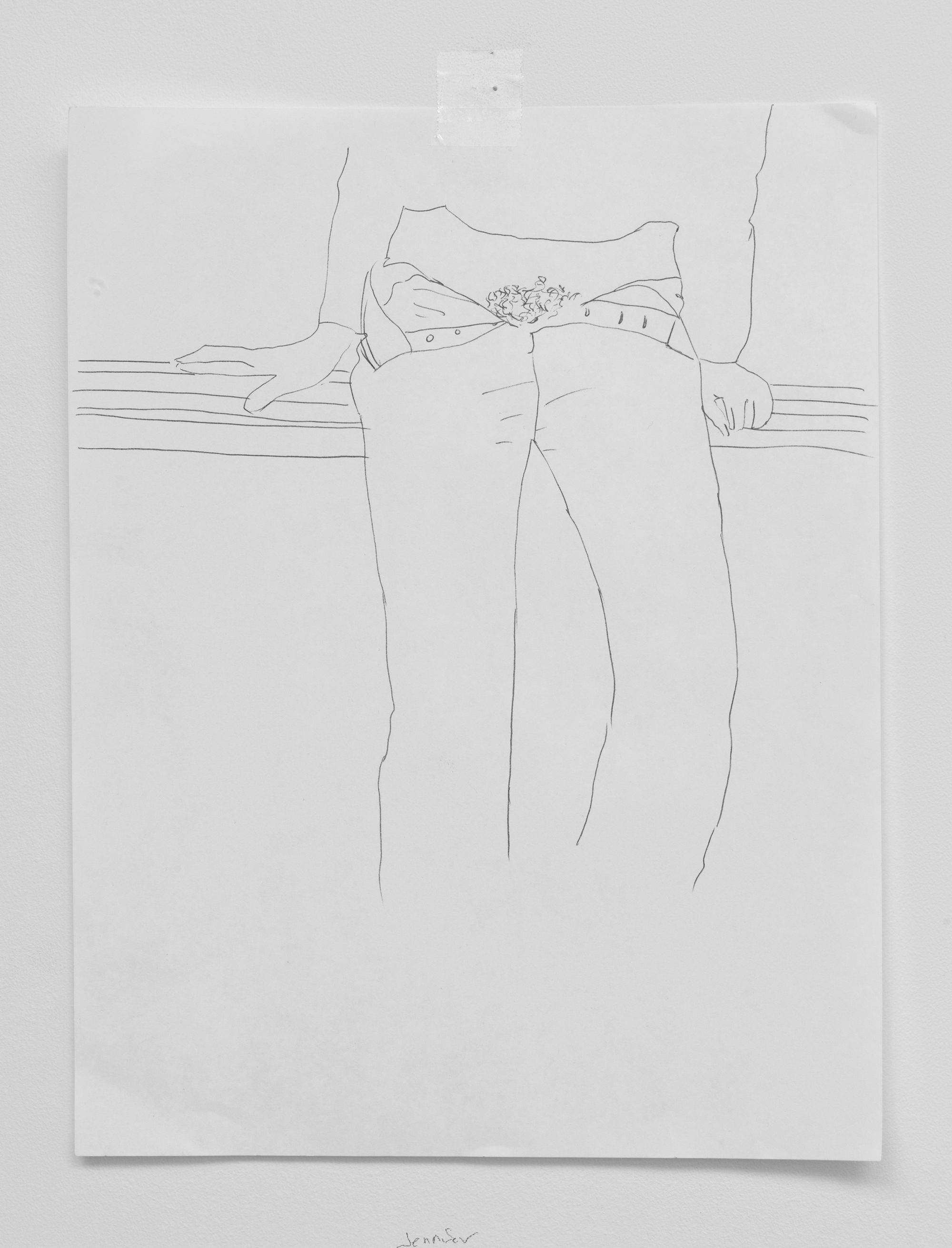

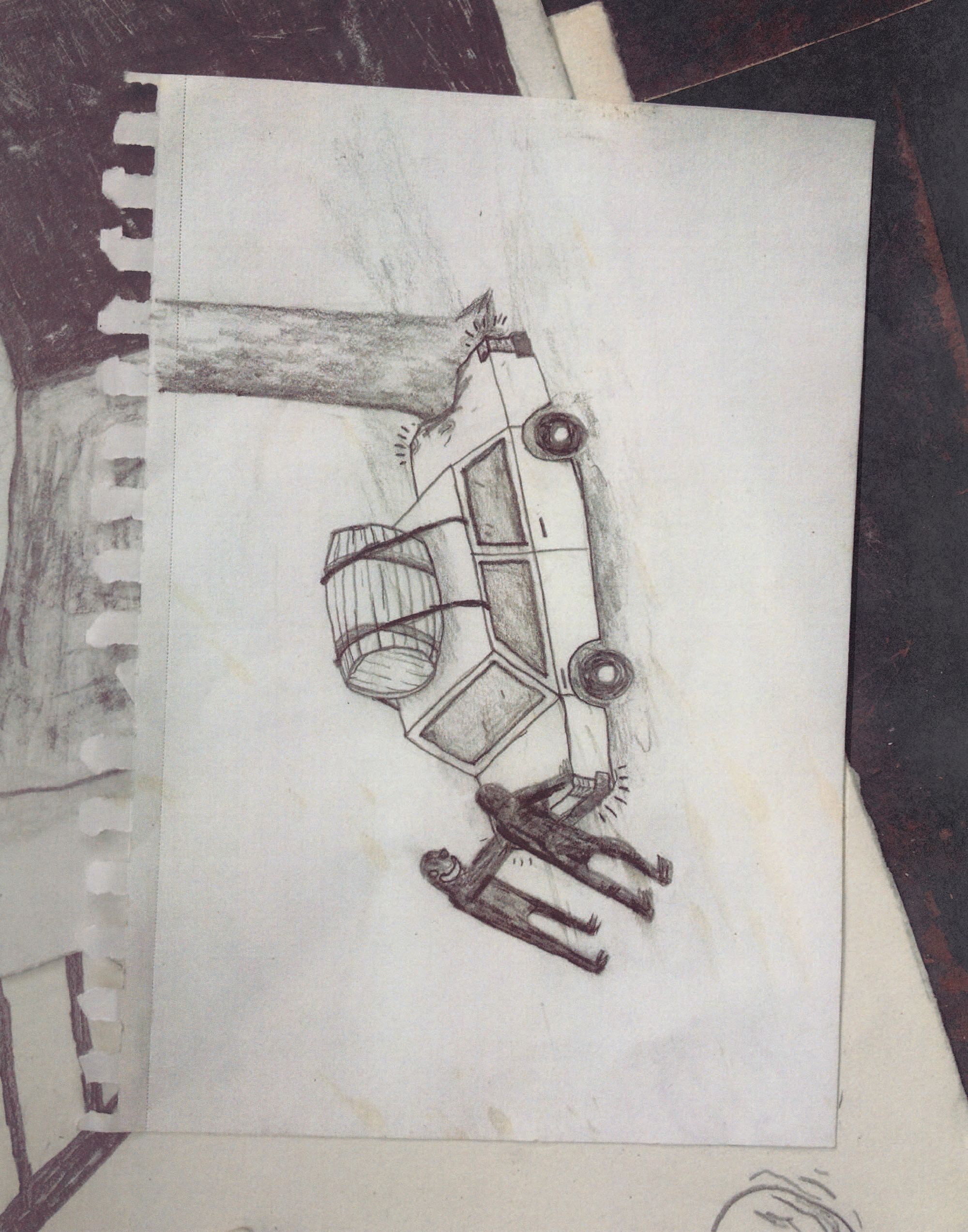

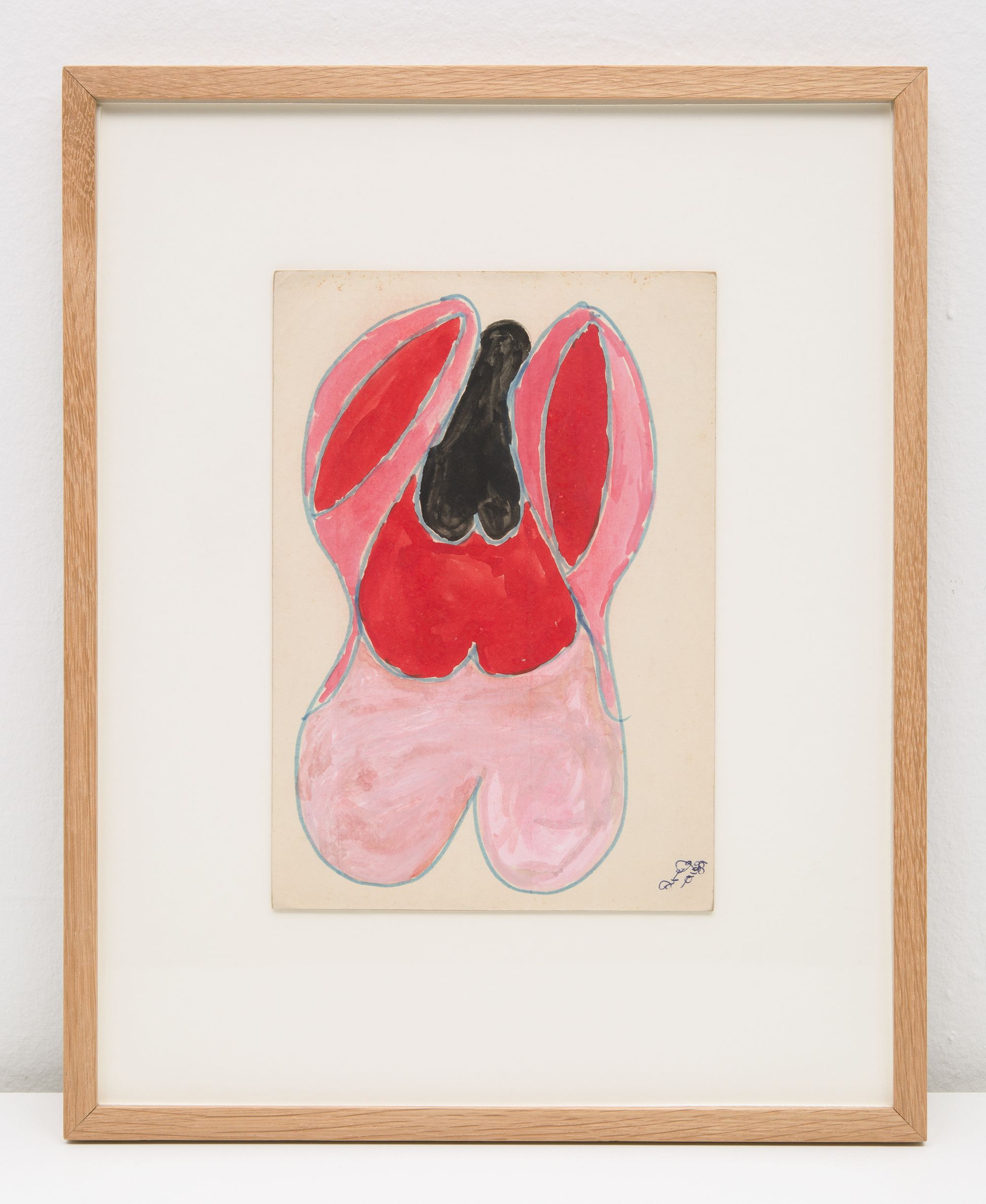

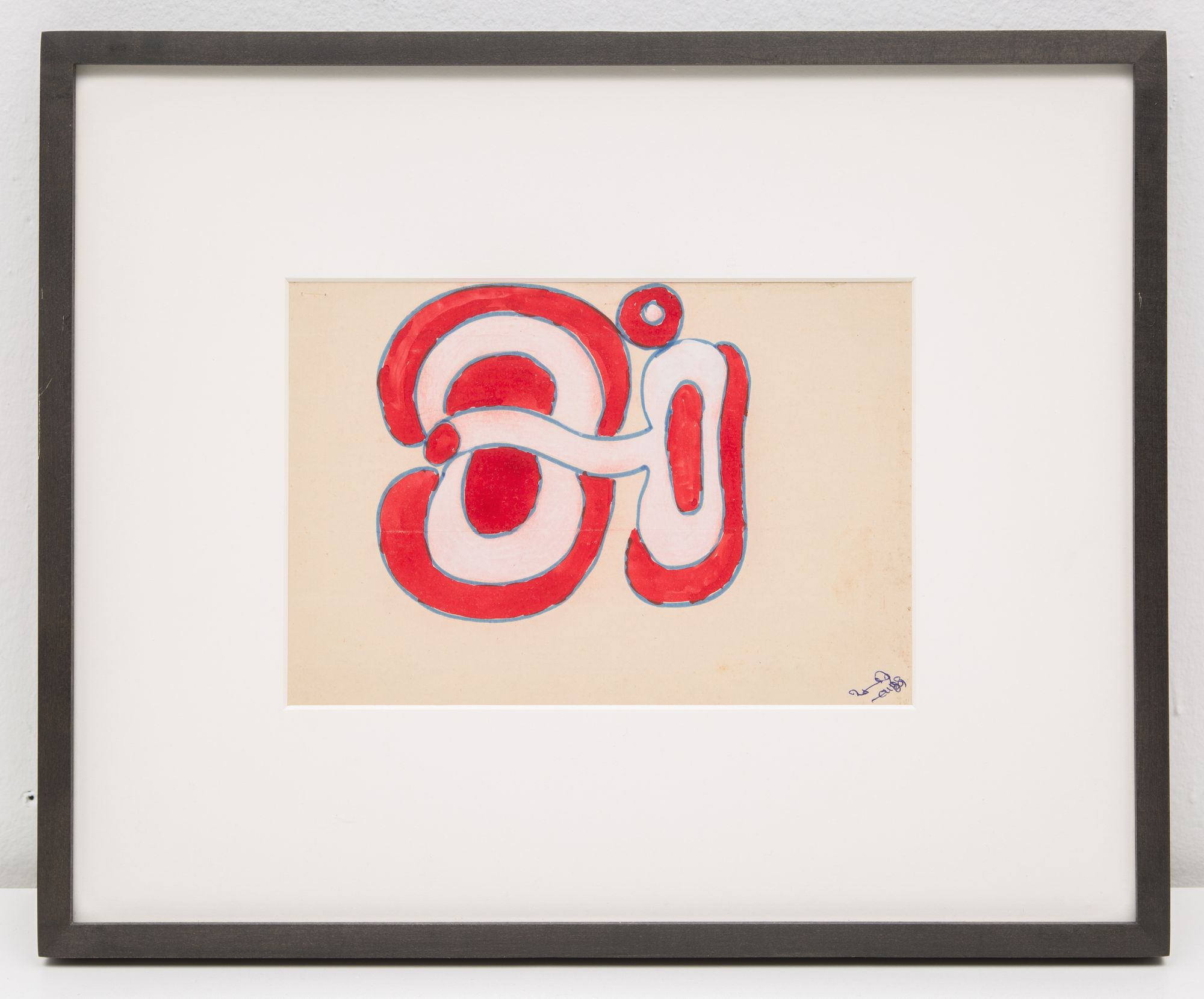

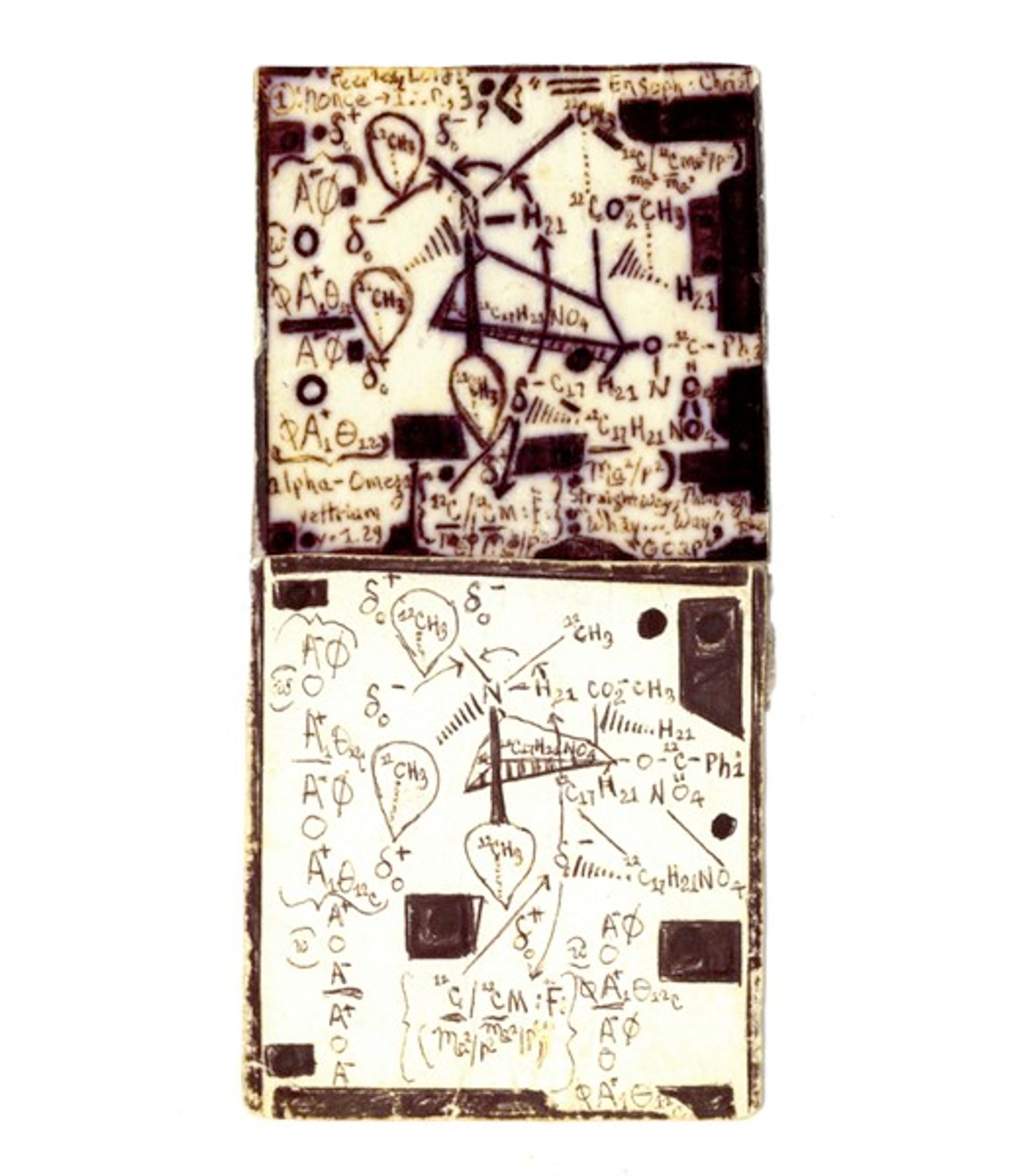

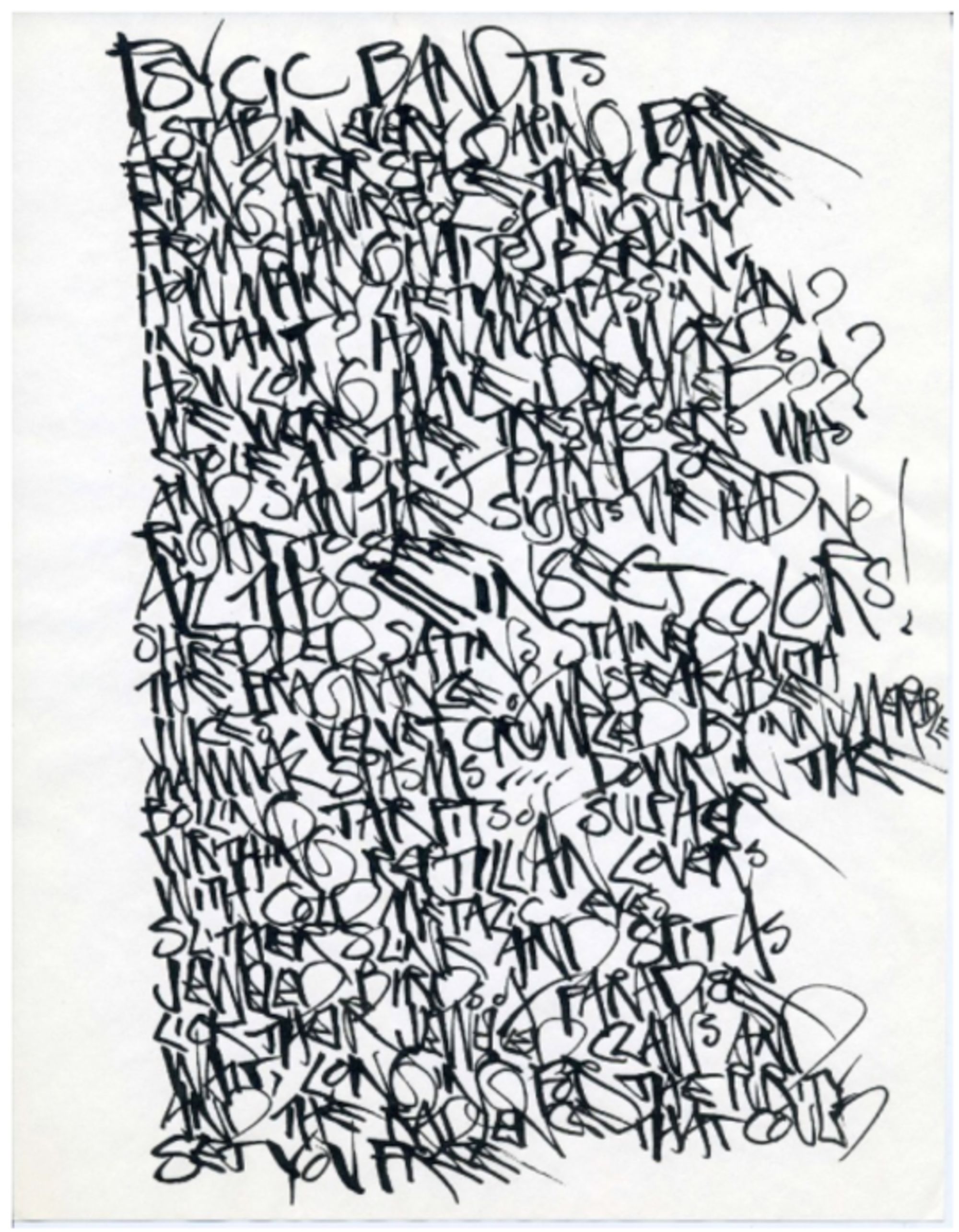

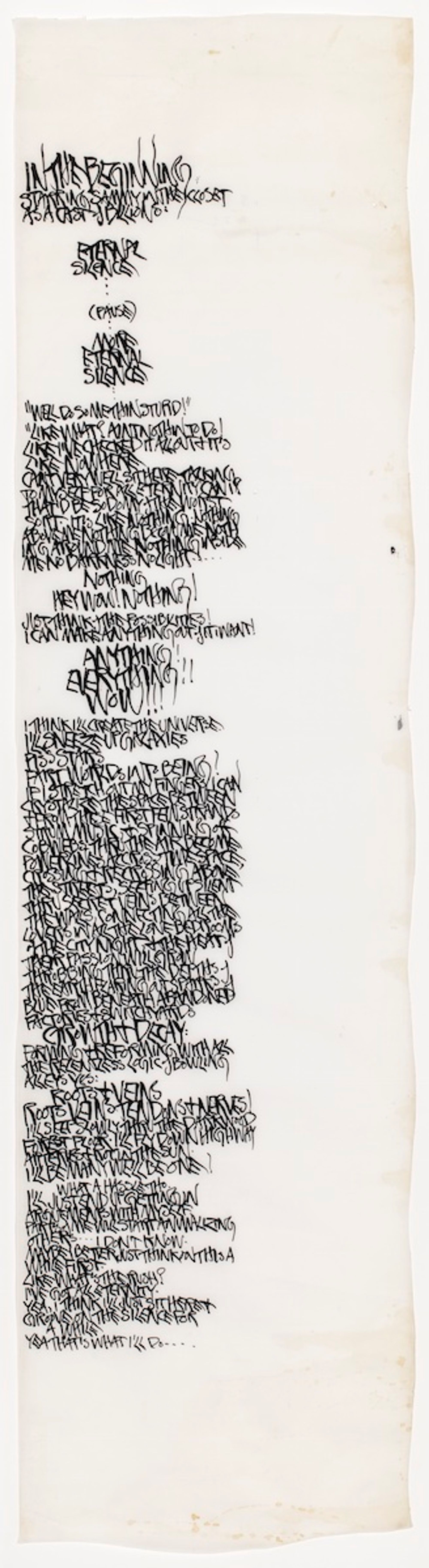

Guy de Cointet, A Page from My Intimate Journal (Part I) —

Guy de Cointet, A Page from My Intimate Journal (Part I) —

Silkscreen on paper

30 x 22 inches

1974

Projects

Readings & Performances

Apr. 1, 2018