Past

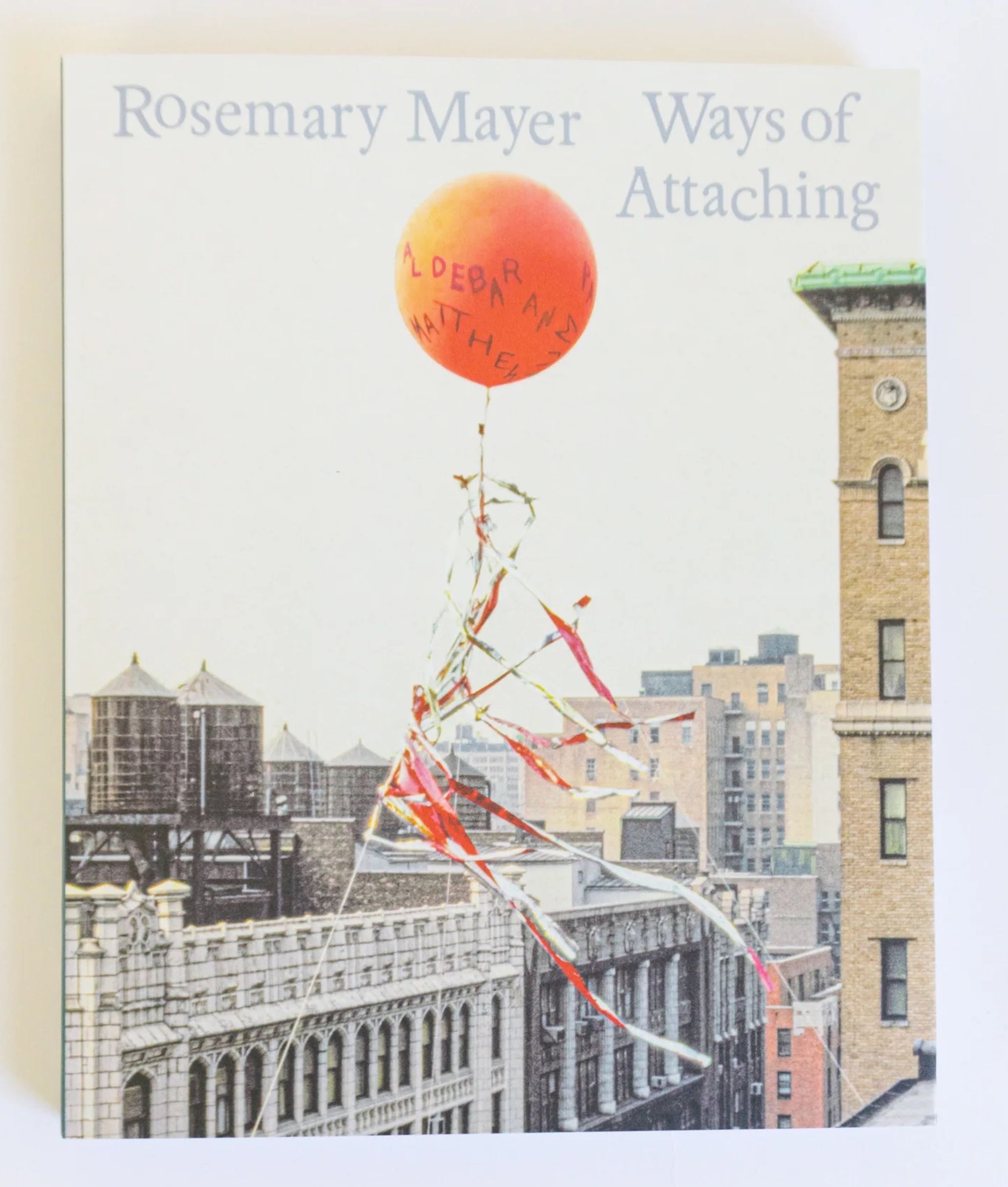

Rosemary Mayer

Pleasures and Possible Celebrations: Rosemary Mayer’s Temporary Monuments, 1977–1981

May 2–June 27, 2021

New York

Gordon Robichaux is pleased to present our first exhibition dedicated to the work of Rosemary Mayer (1943–2014), a prolific artist involved in the New York art scene beginning in the late 1960s. Most well-known for her large-scale sculptures using fabric as the primary material, she also created works on paper, artist books, and outdoor installations, exploring themes of temporality, history, and biography. A pioneer of the feminist art movement, she was a founding member of A.I.R. Gallery—the first cooperative gallery for women in the US—where she presented one of her earliest exhibitions. Gordon Robichaux’s presentation is Mayer’s most recent in New York since a 2016 show at Southfirst Gallery, and will be followed by a survey at the Swiss Institute in September 2021.

Installed across both spaces at Gordon Robichaux, the exhibition features a selection of drawings and documentation related to ephemeral installations and unrealized projects with balloons from the late 1970s, including Spell, Some Days in April, and Connections, part of a body of work she called “Temporary Monuments.” This is the first occasion the work will be on display since it was originally exhibited in the late 1970s and early ’80s. Two related sculptures will also be on view. Scarecrow (model) for a field, made with fabric, wood, and ribbons, is a proposal for an unrealized Temporary Monument and the only extant sculpture from this period. 17th Street Ghost is a site-responsive presentation of one of Mayer’s ephemeral “Ghosts” sculptures, conceived for this exhibition by the Estate of Rosemary Mayer.

In conjunction with the exhibition, Gordon Robichaux commissioned the following text from the artist’s niece Marie Warsh, in which she considers the work and ideas in depth.

Install (12)

To give me a hold, make me a place, in time and seasons, mark them this way and think of the other, older ways people marked years and seasons, of circling ghosts around days with religious ceremonies, birthdays, new clothes for different seasons.

—Rosemary Mayer, Poster for Spell, 1977

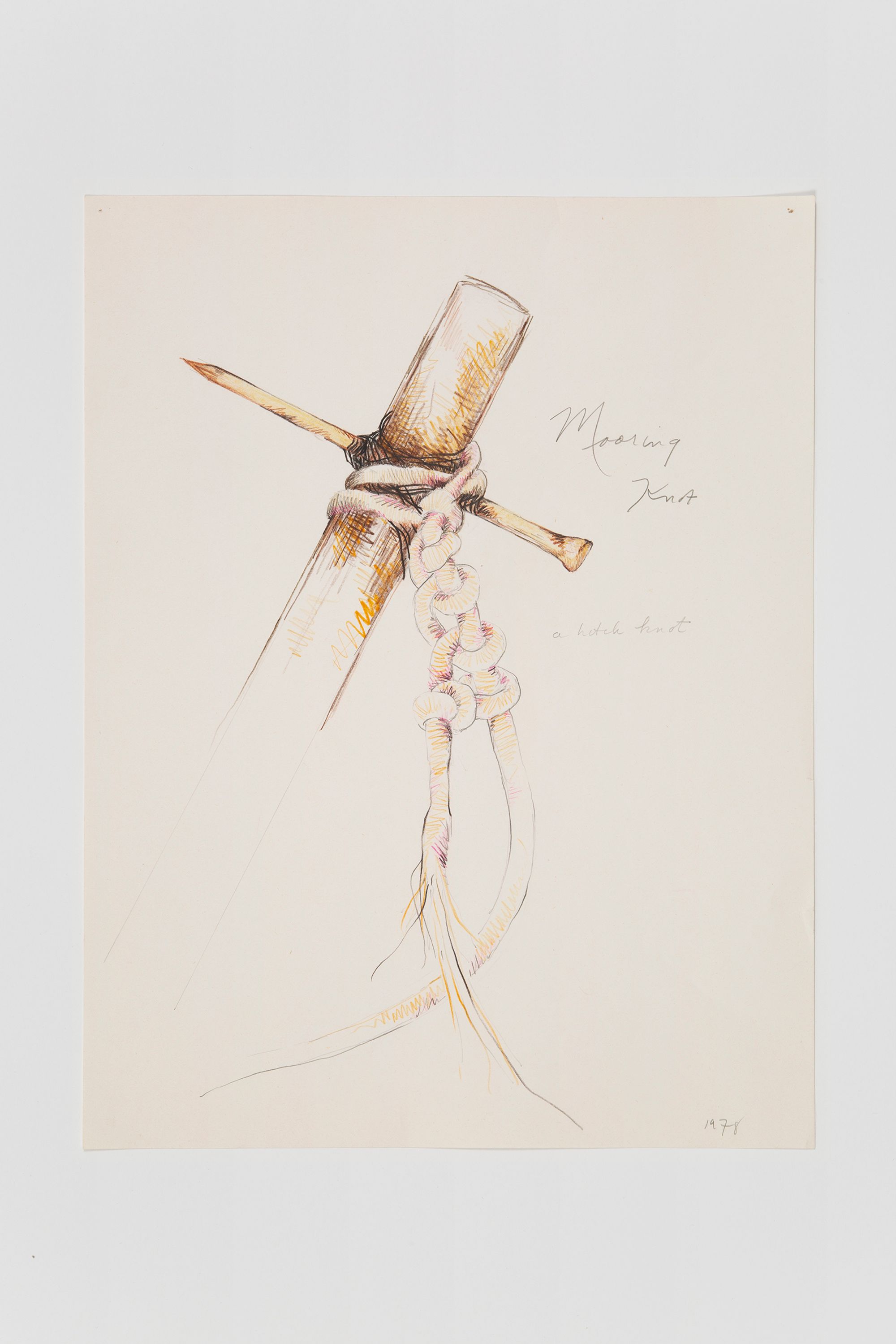

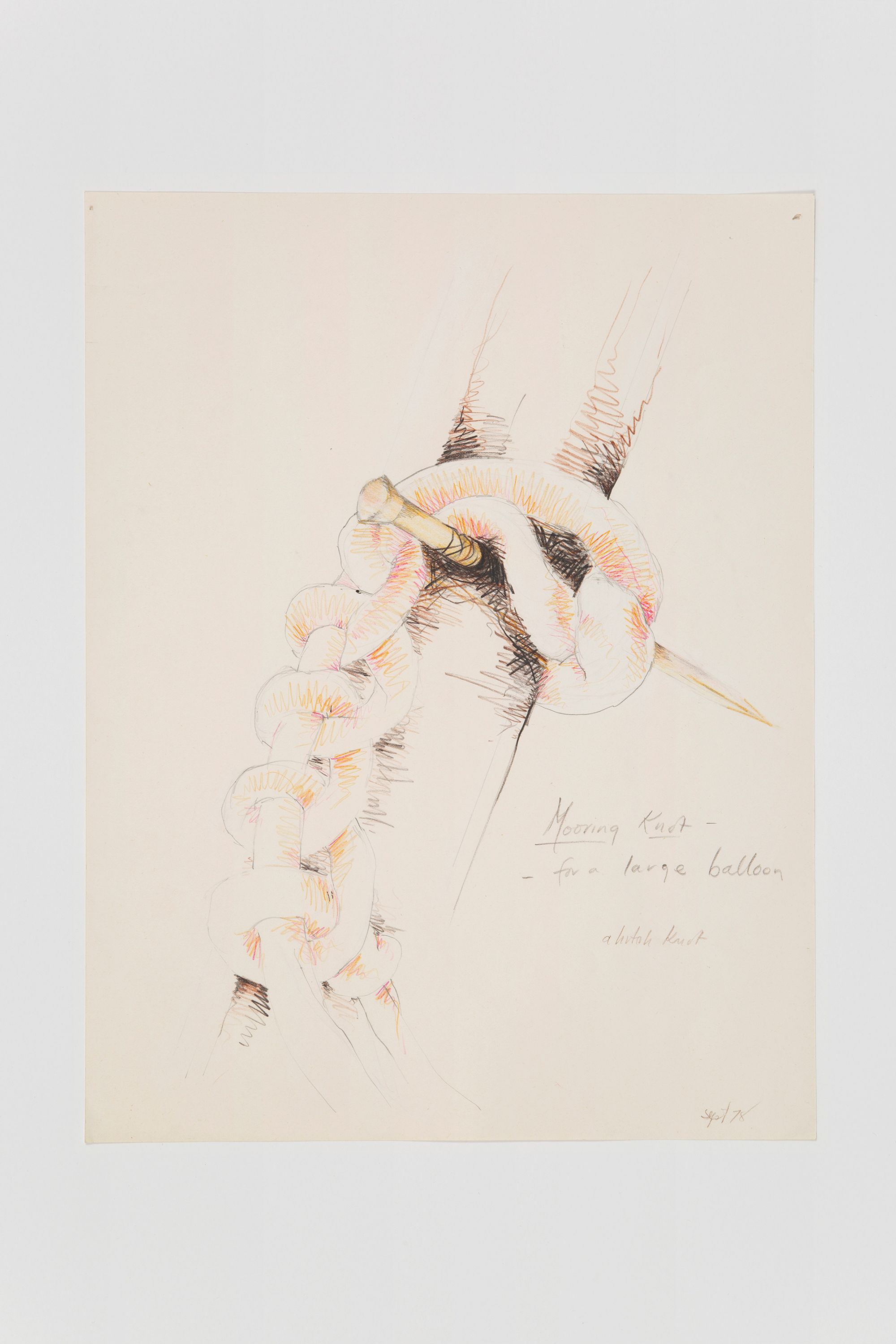

Beginning in 1977, Mayer embarked on a series of installations featuring large weather balloons filled with helium. The works, which she sometimes called “floating sculptures,” had different purposes: one was to celebrate a birthday, another to honor the dead, and yet another to welcome spring. But these and several unrealized projects all explored the balloon as a metaphor for the passage of time, at once celebratory, fleeting, and elegiac. They integrated fabric, ribbons, and cords, materials used in her well-known sculptures of the earlier 1970s, which were homages to women lost to history. They also drew from celebrations of the past, such as ancient May Day rituals and the spectacles of European courts during the Renaissance. The balloon projects were the first in a larger body of work she called “Temporary Monuments” that over time incorporated other fugitive materials and installations. Snow People (1979), the most well-known, was a group of figures made out of snow dedicated to the historic townspeople of Lenox, Massachusetts. Mayer also became interested in tents, envisioning them as sites for gathering and seasonal celebration, which she explored in drawings, writing, and the 1981 installation, Moon Tent.

In her creation of impermanent works that sought to connect individuals and communities to time, place, and nature, Mayer challenged traditional and patriarchal notions of commemoration and monumentality in ways that prefigure current debates over public art and monuments. She documented her ephemeral balloon installations in a great range of media—drawings, photography, posters, flyers, artist books, and writings that increased the visibility of the work while evidencing her lifelong exploration of the relationship between text and image.

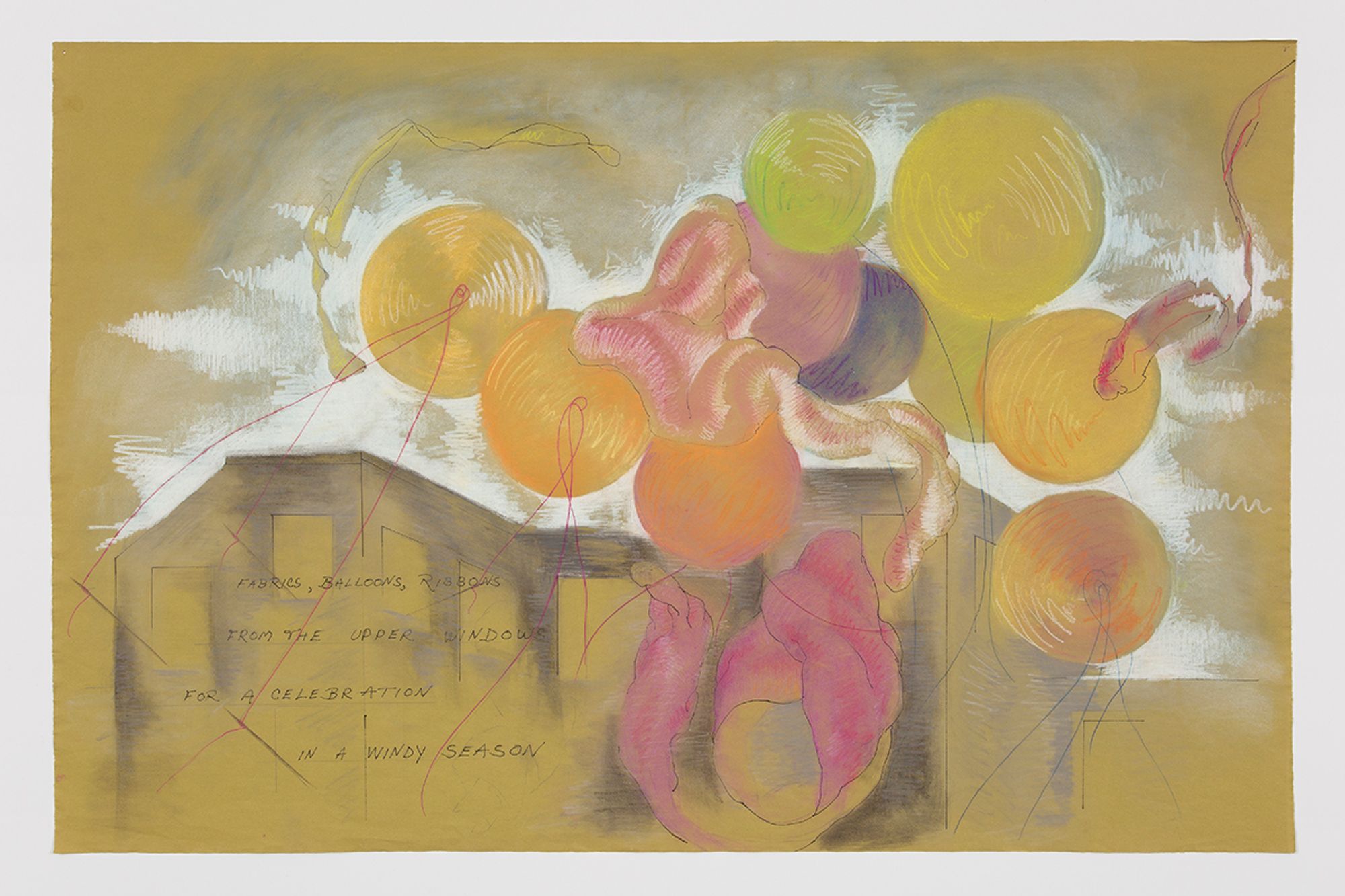

For her first project, Spell (1977), she planned for large helium-filled weather balloons, painted with the phrases “Iris Return,” “Crocus Return,” and “Hyacinth Return,” to rise above a newly opened farmer’s market in Jamaica, Queens, trailing swaths of fabric. She created a series of posters announcing the project and commissioned a photographer to document the installation. While Mayer’s vision was thwarted by high winds, which tangled the cords and fabrics, she was pleased with how the photographs captured the collaborative process of working on the installation and its relationship to the site. She combined the photographs with a text she wrote later into an artist book. Later, she described the work as “between sculpture and celebration, decoration and private magic.”

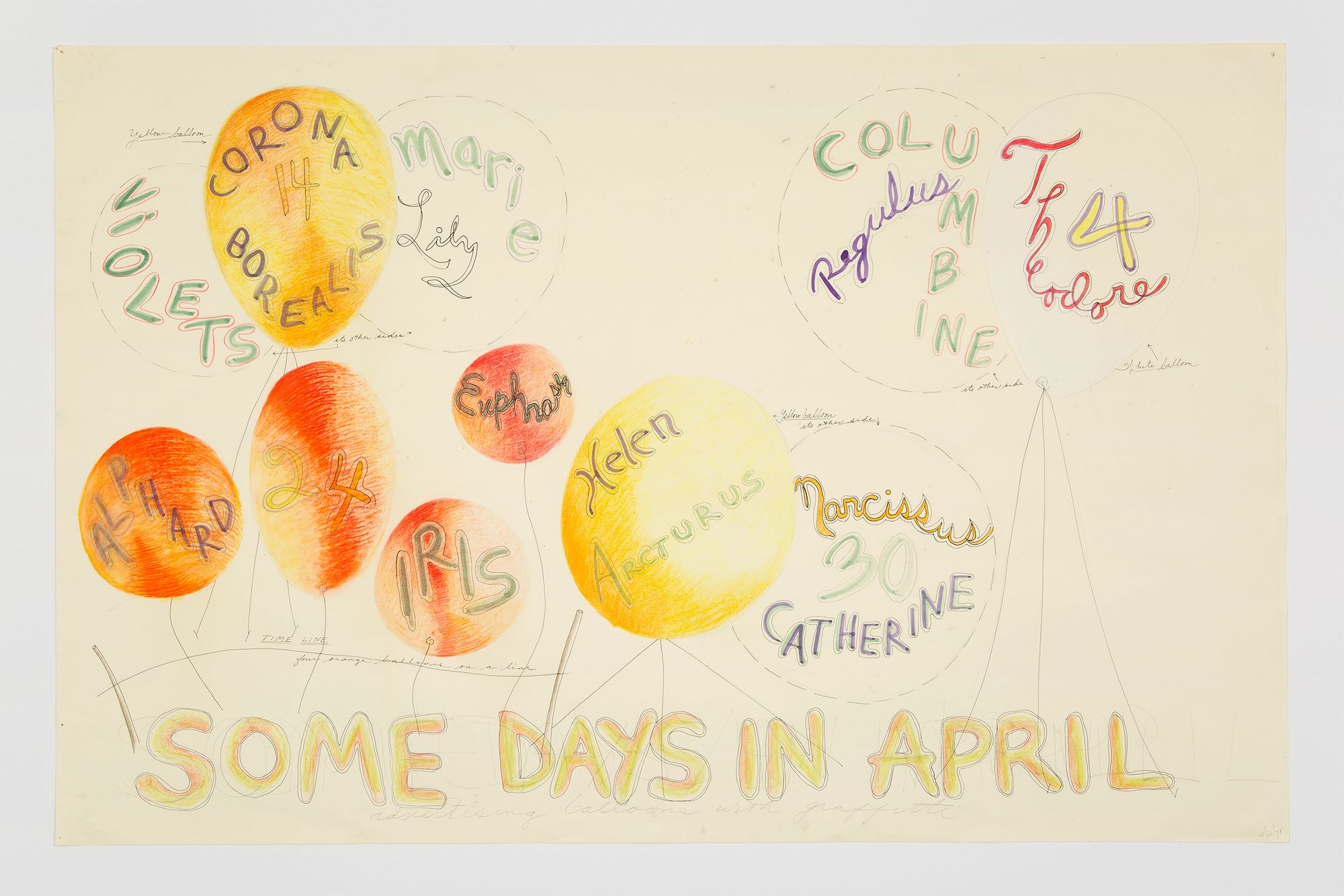

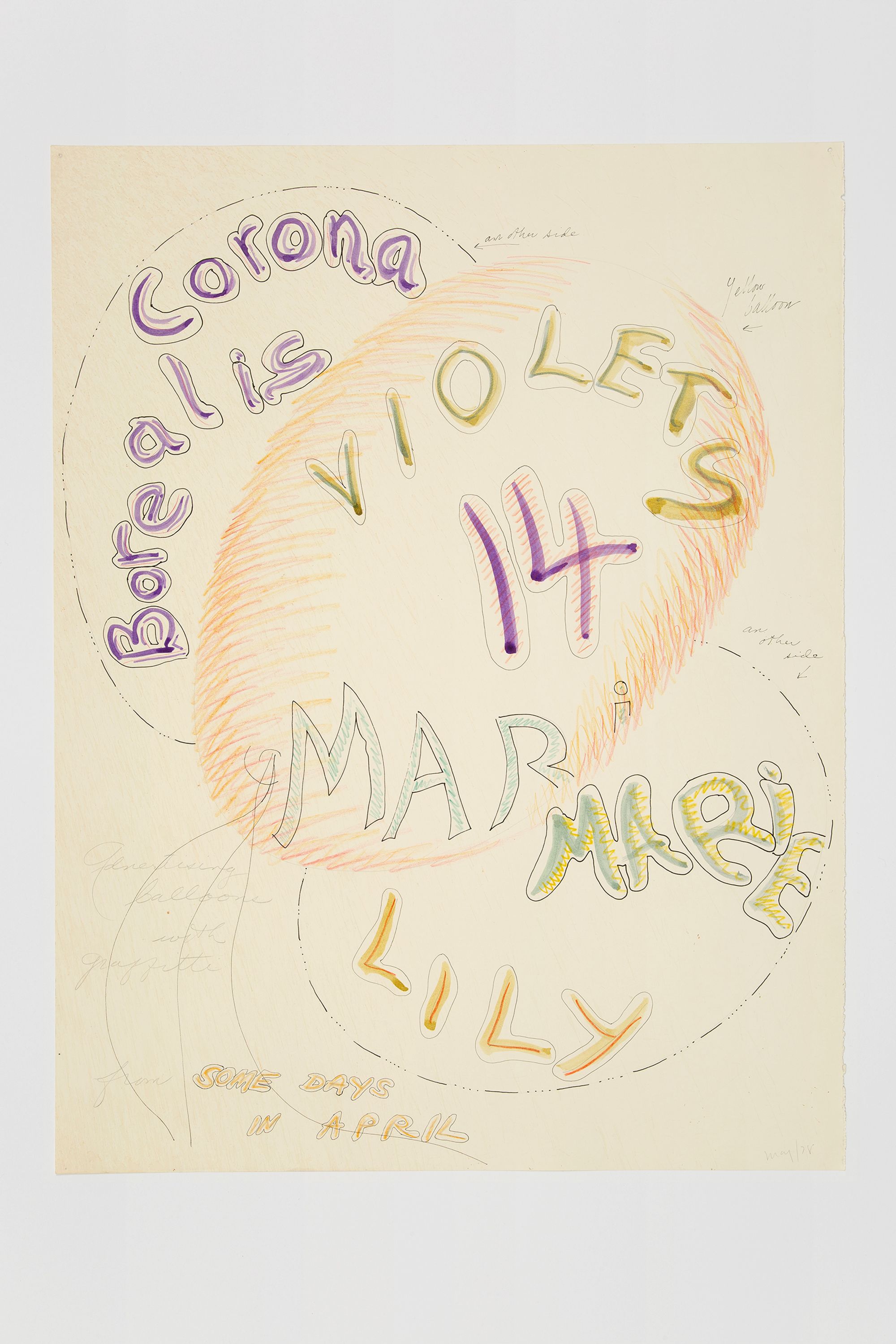

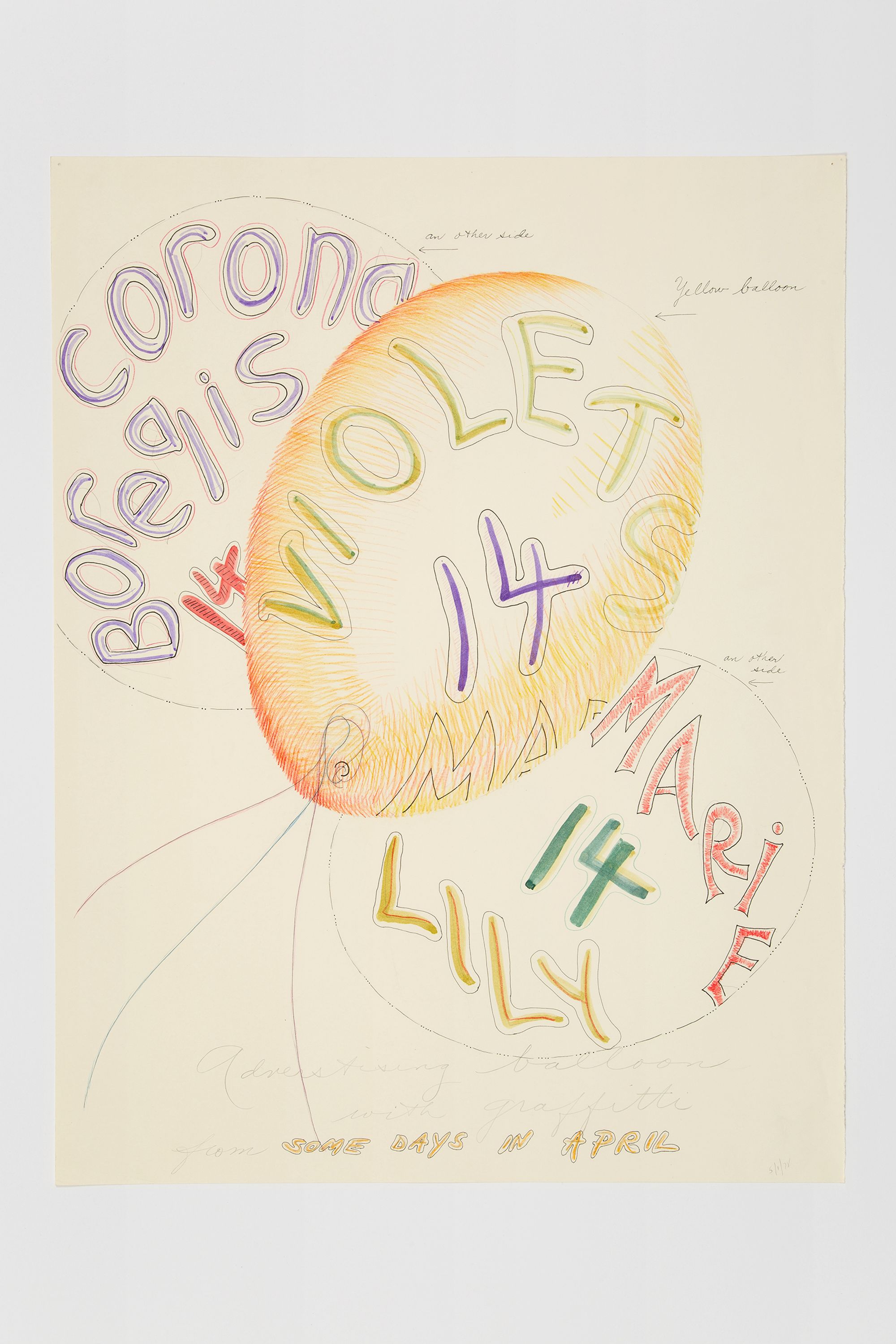

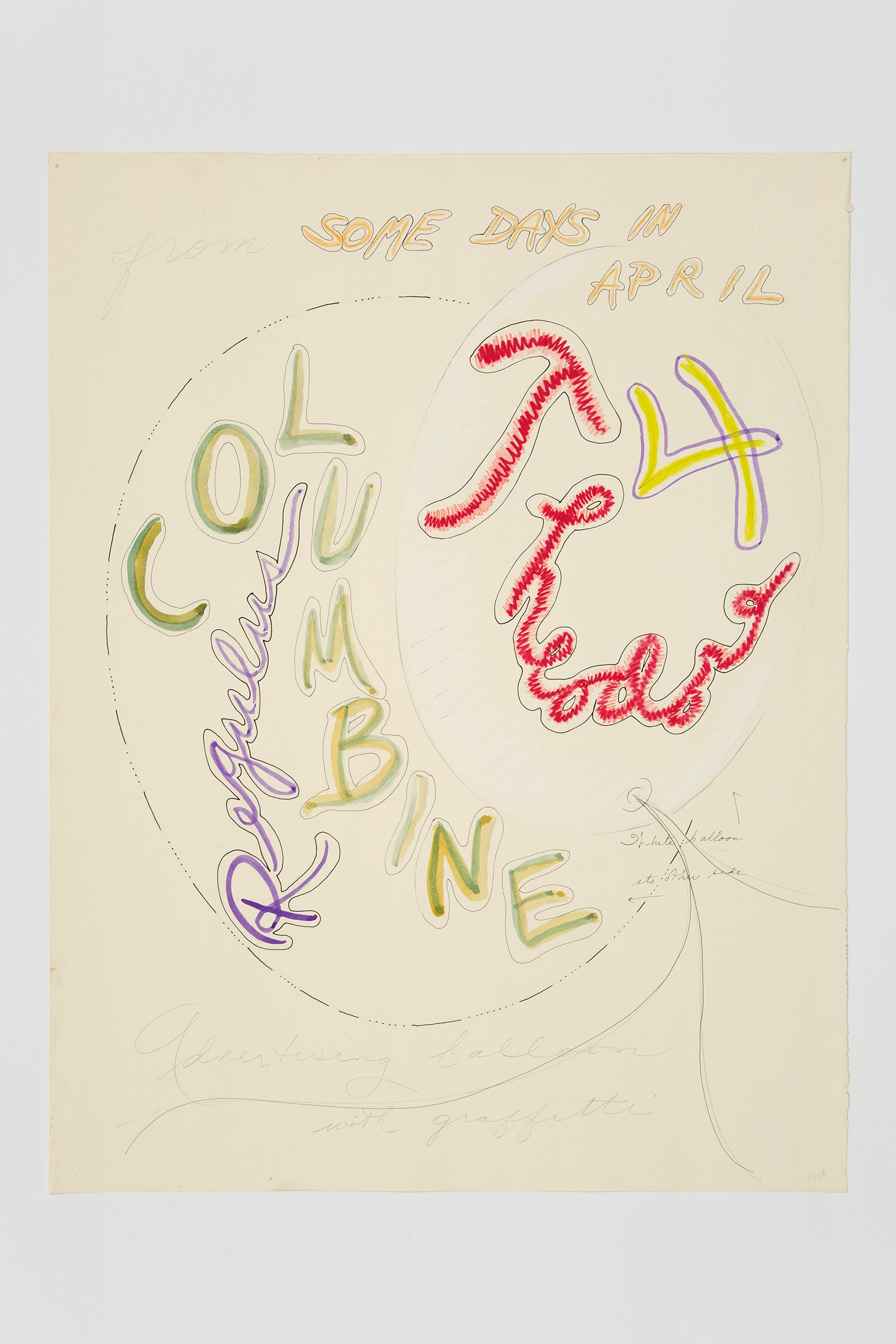

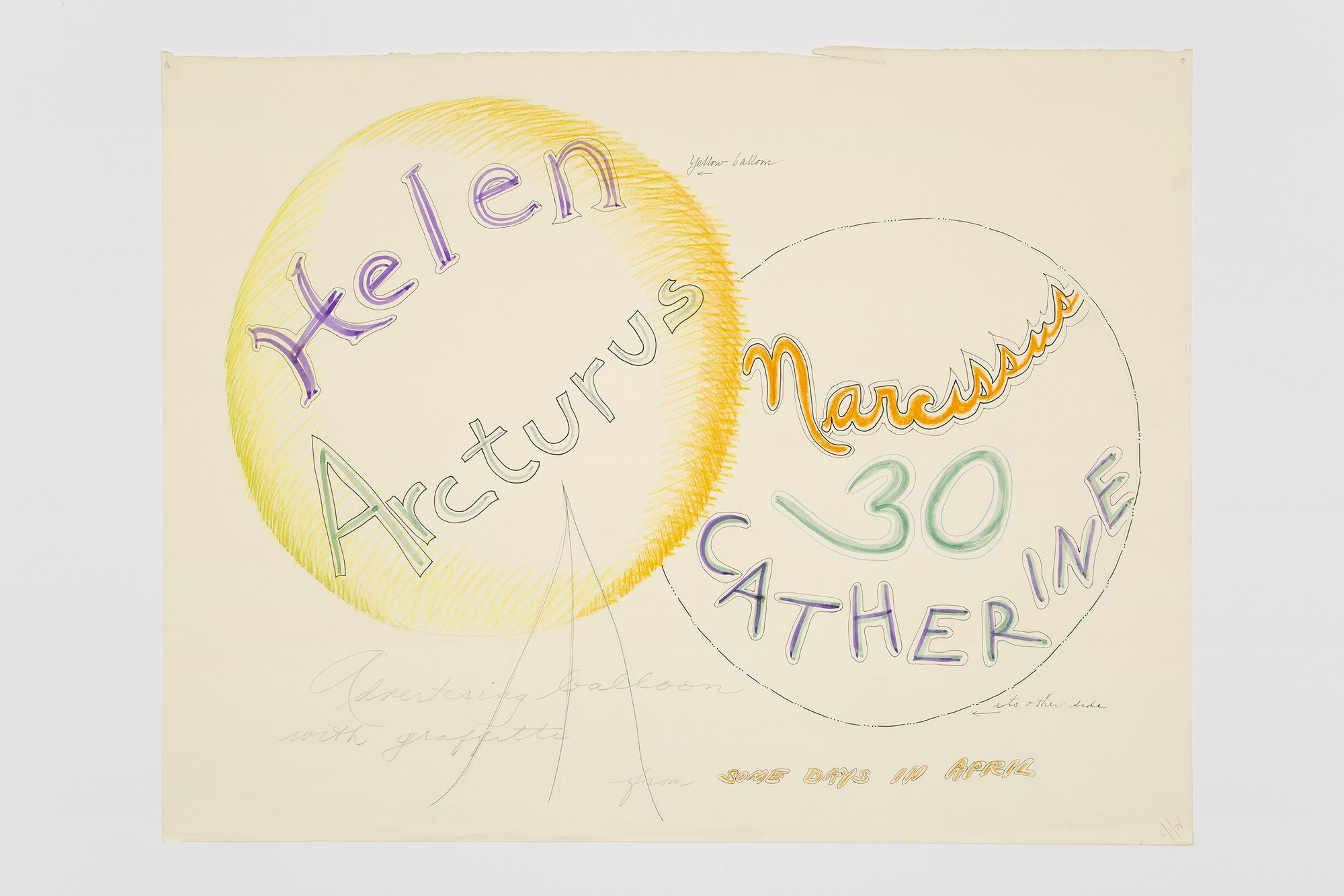

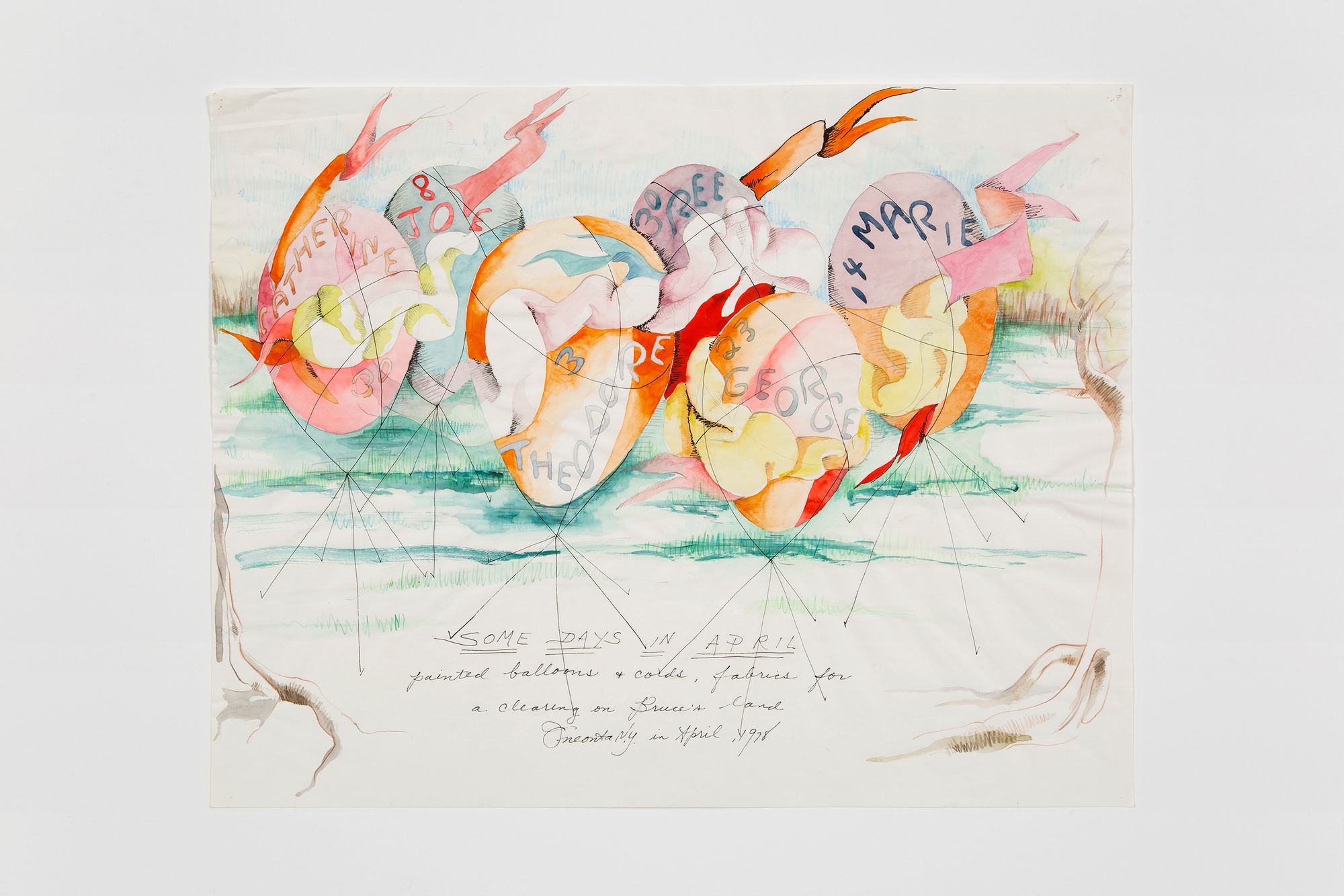

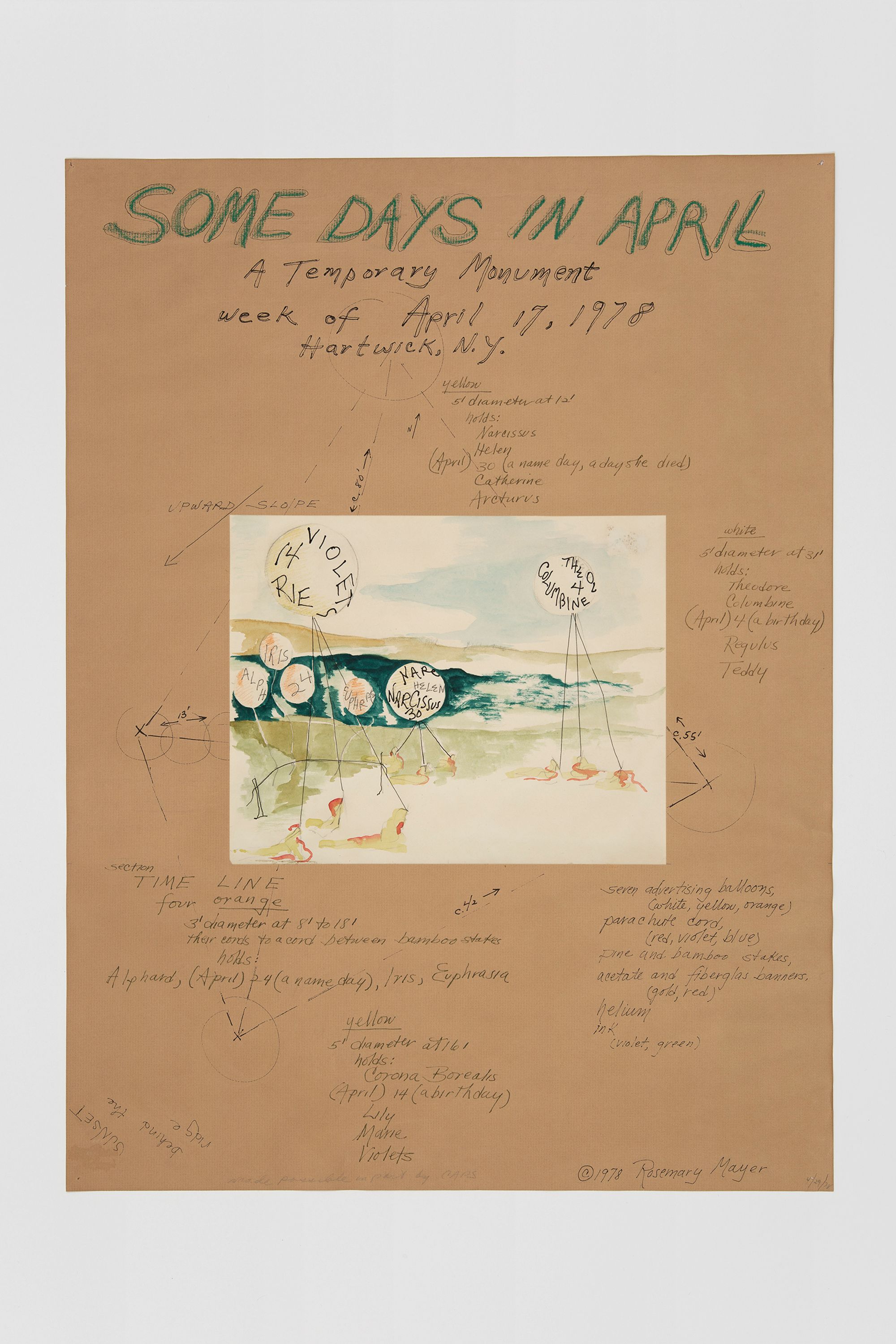

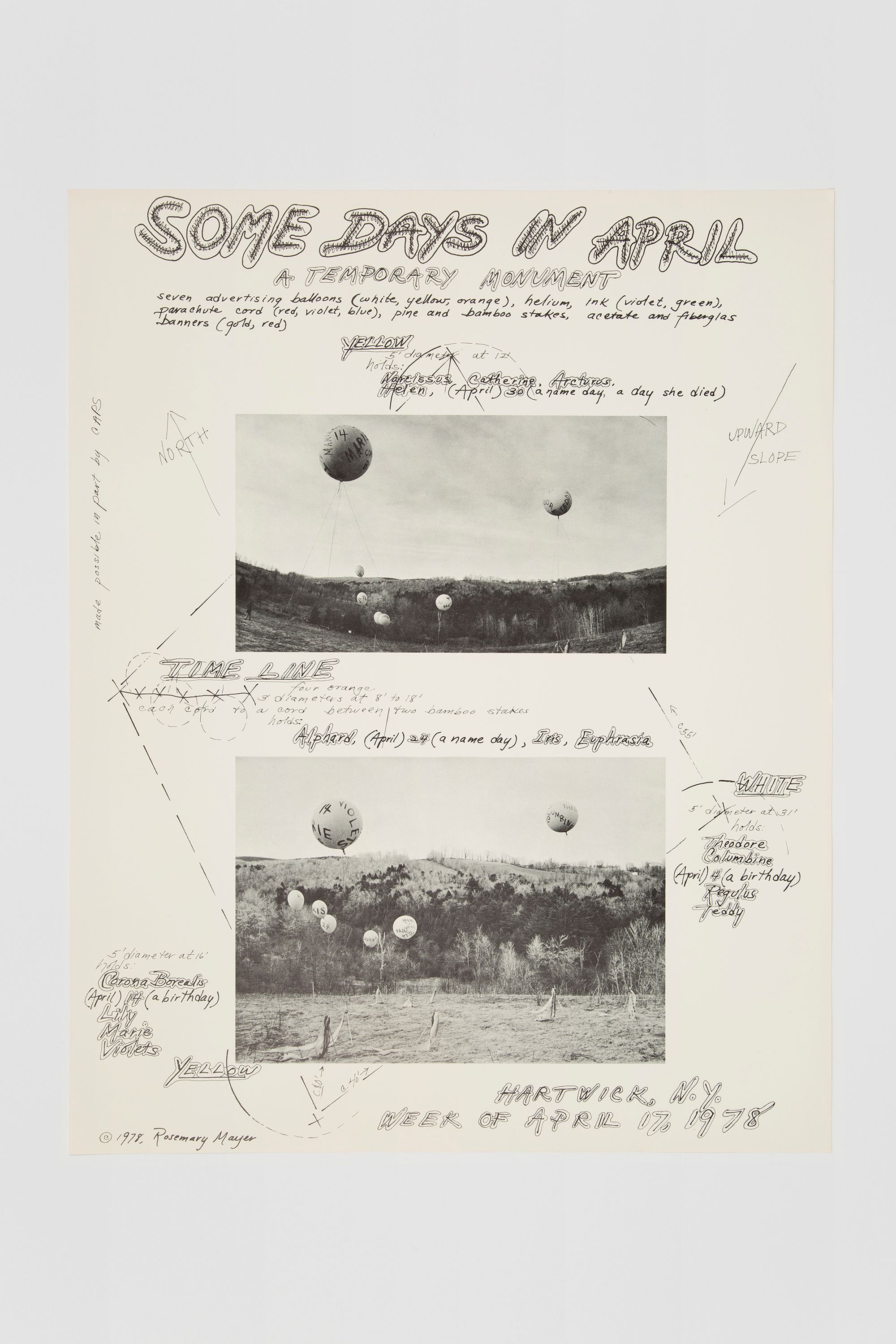

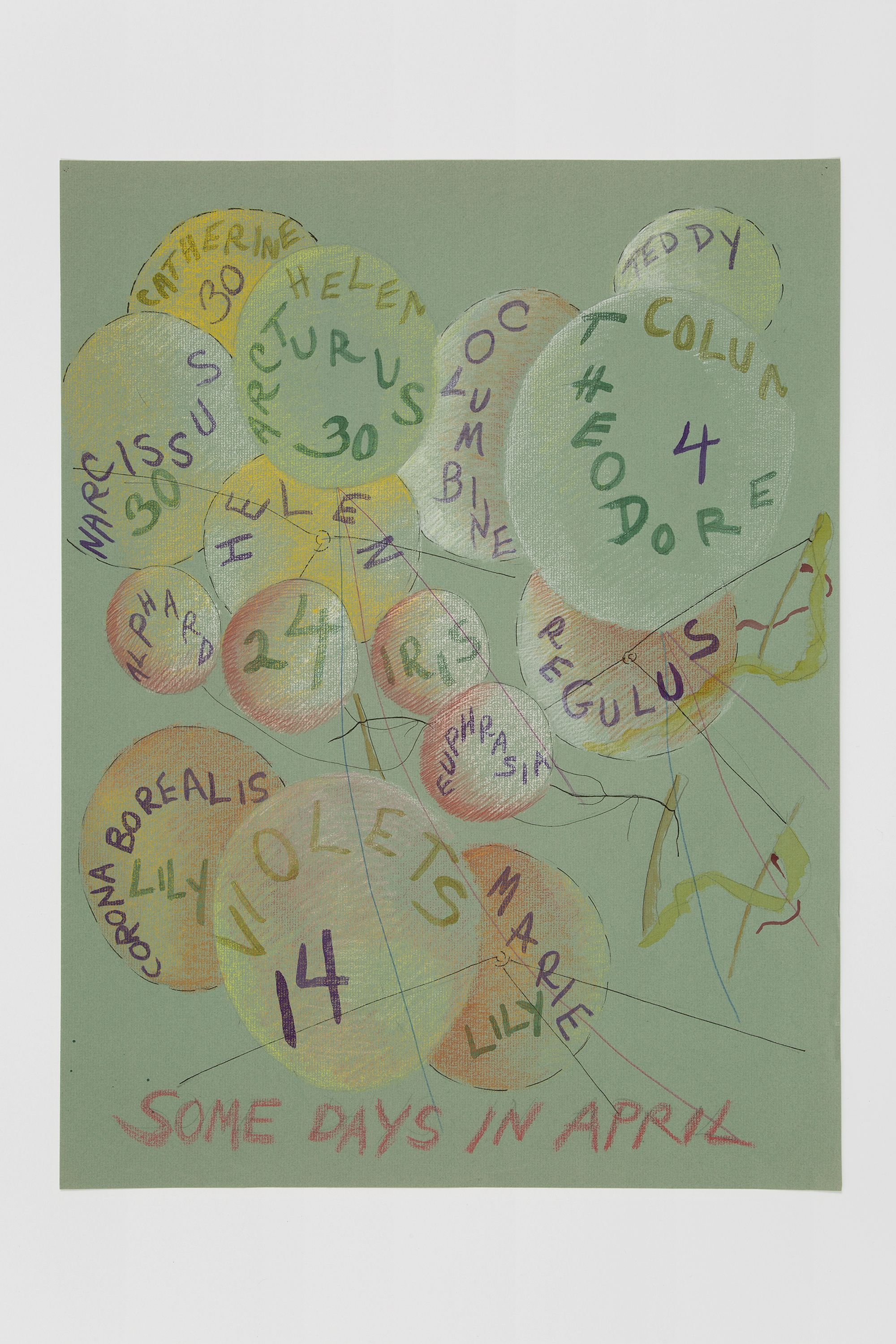

Some Days in April, her next project, was created in April 1978 in an empty field in upstate New York, ensuring its documentation even more essential as a way of “making it public,” as she described the process of sharing the work. The installation of seven balloons tethered to the ground was both a celebration of spring and a memorial. It honored her parents, who both died in the 1950s and both had birthdays in April, and her friend, the artist Ree Morton, who had died in April the year before. She painted the balloons with the name of the person, the day associated with them, and the names of flowers and stars visible in April. (Helen was Morton’s given name.) In addition to taking photographs, she created a poster that she mailed to friends and art institutions, a series of drawings that she exhibited at galleries, and an artist book.

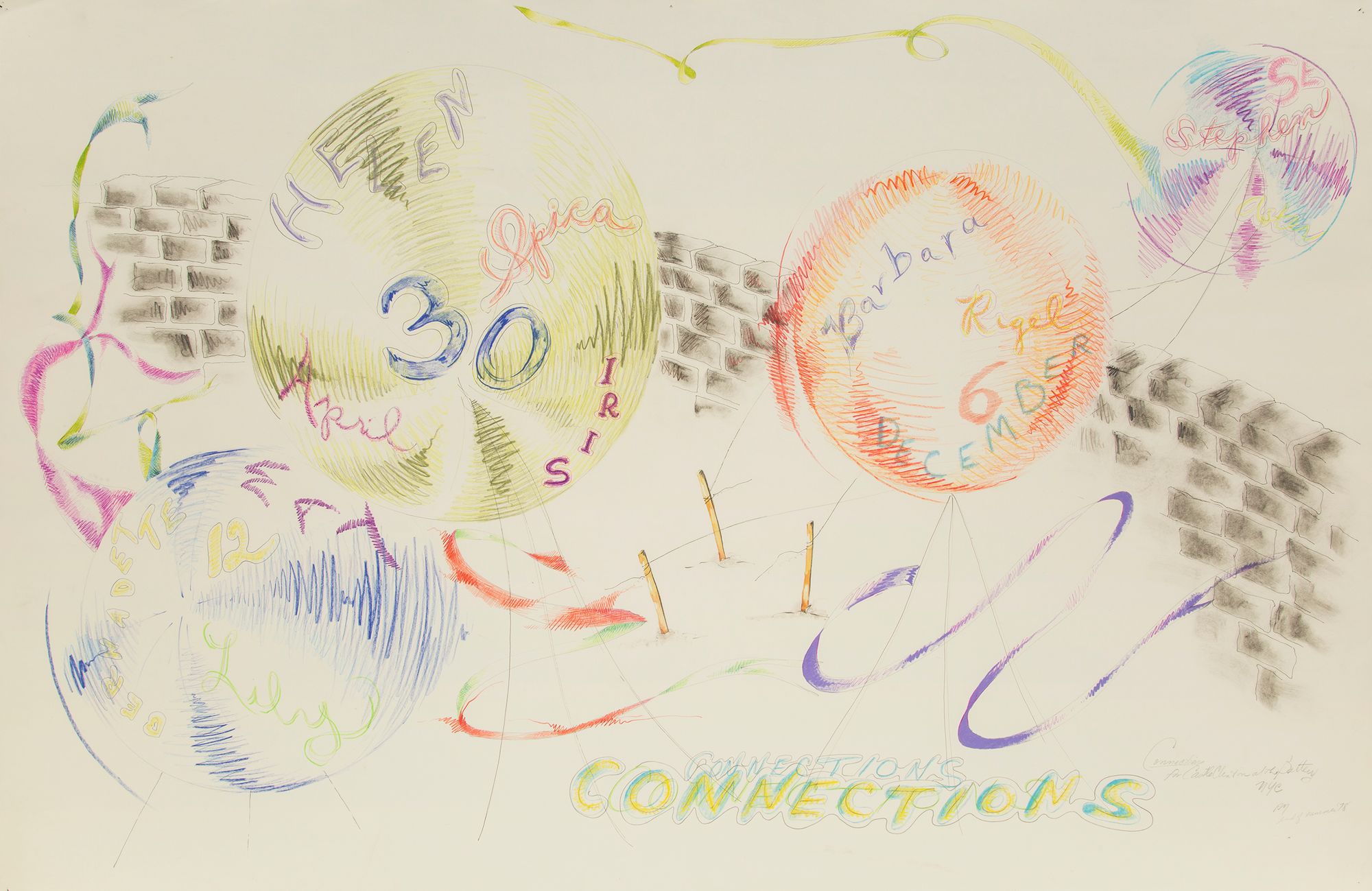

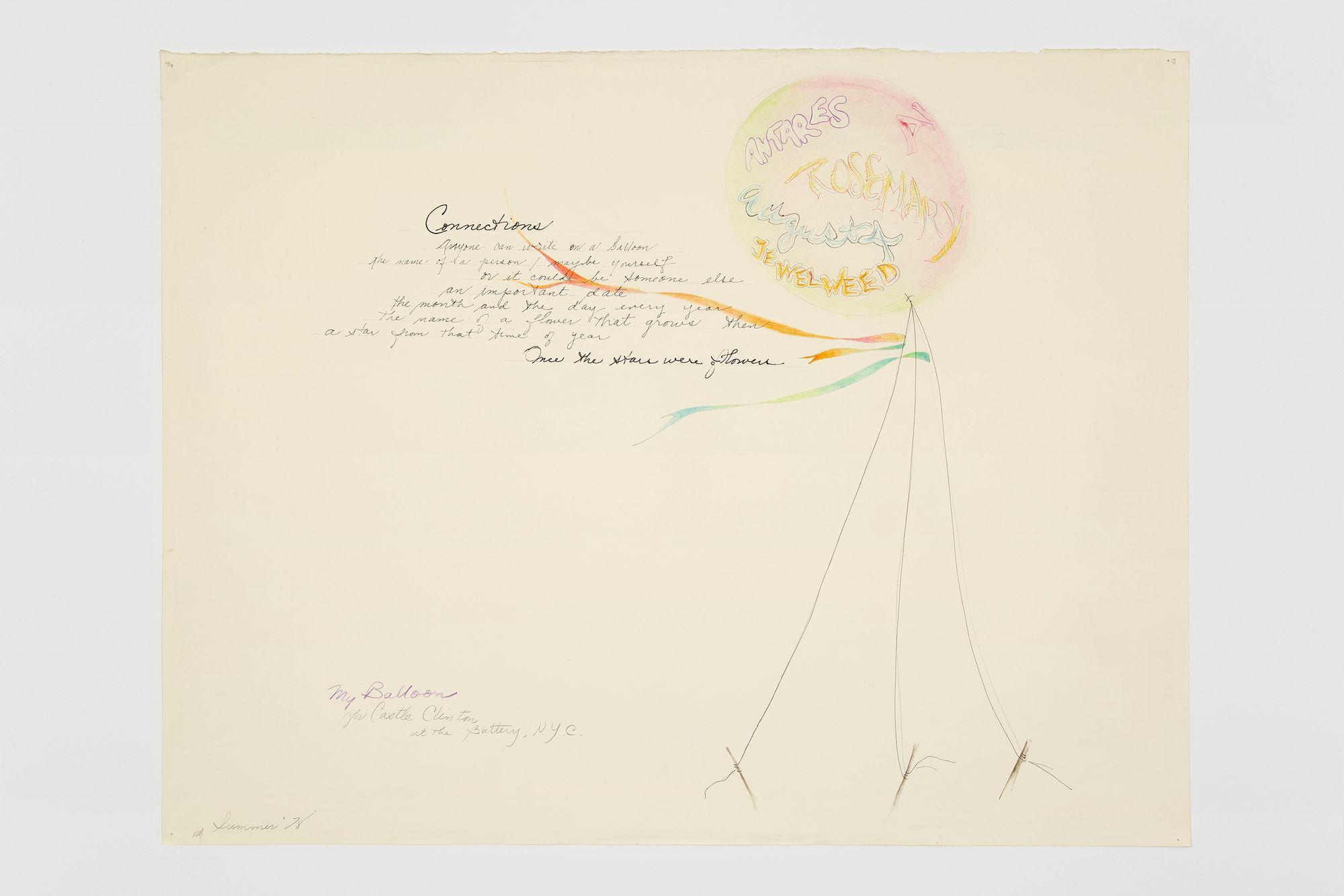

This concept of a balloon as a monument to an individual was further explored in Connections, a proposal for a project envisioned for Castle Clinton, the historic fort in Manhattan’s Battery Park. She described this work as a “community celebration,” which involved children ages twelve and thirteen choosing a balloon and decorating it with the name of a person and, like Some Days in April, a star and flower. She connected children writing on their balloons to the way people made marks through graffiti, which in 1978 covered the city. When the proposal submitted to a public art organization was not accepted, she created a series of drawings that imagined how it could have appeared, depicting the roofless fort overflowing with balloons, which would blow away or deflate over time.

Scarecrow (model) for a field (1978–79) is the only extant sculpture from this period, making it the only “permanent” Temporary Monument. Like several other unrealized projects, she considered this work an “impossible sculpture,” and its title and notes in her archives suggest that she envisioned it for a field in a rural setting. The scarecrow was for Mayer a symbol of evanescence, a vehicle for seasonal ritual and celebration. She wrote about how scarecrows “announced the growing season, flapping in wind in mimicry of human forms. In fall, after harvest, they fell apart in the fields....” In evoking the human figure and presence, they also created a bridge to her earlier work. Art critic Lawrence Alloway, writing about her large-scale fabric sculptures from the early 1970s, connected them to the Surrealist concept of the personnage, which he defined as a “totemic, ancestral, or regressive image manifested in forms that relied on the human contour, but without specifying details.”

The ghostly form of Scarecrow, which was constructed out of fabric draped on a frame made of thin, wooden rods, led to a series of installations that Mayer called “Ghosts,” which she created in 1981. Conceived of as ephemeral, site-responsive sculptures for gallery spaces, they reveal Mayer’s attempt to bring the Temporary Monument ideas indoors. Like balloons and scarecrows, ghosts were another mode of exploring impermanence and the constellations of connections between place, time, and people. She wrote in one essay, “No one has ever seen a ghost. They’re visible only for seconds and even then they change. They live in the fall of a sleeve or a skirt, the shapes in a coat laid over a chair. When the light changes they’re different or gone.” Instead of fabric draped on the rods, she experimented with a variety of light, translucent materials, such as paper, glassine, cellophane, and plastic, drawn to the different ways they interacted with light and how these effects could fill a space with illusory presence. Painting the rods gold further dematerialized the work, while the addition of brightly colored ribbons and cords were decorative flourishes that also grounded the seemingly fragile structure.

For the occasion of this exhibition, the Estate of Rosemary Mayer conceived of a new presentation of Mayer’s “Ghosts,” entitled 17th Street Ghost and created with the assistance of artist Amanda Friedman. Drawing from Mayer’s extensive documentation of this body of work as well as her writings, 17th Street Ghost is intended as a form of seasonal celebration. This is the second time the Estate has created a new work from this series; the first was in February 2020 in collaboration with the artist Nick Mauss for his exhibition Bizarre Silks, Private Imaginings and Narrative Facts, etc. at Kunsthalle Basel.

Mayer described her first Temporary Monument, Spell, as a “magic rite to ensure the arrival of spring,” with its helium-filled balloons soaring upwards like the growth of plants. 17th Street Ghost is created as a similar ritual, to welcome the growing, warming light that promises summer. It is named for its location and the orientation of the room to the urban scene, with its north/northwest view, the direction of sunrise during this time of year. The light streaming in through its windows will increase as the days approach the summer solstice, at the end of the exhibition. With no trees or other plants visible in the view out the windows, light is the evidence of the changing season. In Suite 907, 17th Street Ghost becomes the plant, heliotropic, responding to the direction and warmth of the sun.

For Mayer, light was material and performance, and observing it as it changed over time was a source of pleasure and solace. “Light, as anyone knows, is the whole show,” she wrote. During this ongoing pandemic that has in many ways redefined our relationship to time, Rosemary Mayer’s “Temporary Monuments” have new resonance, through their invitation to the collective observation and quiet celebration of the details of the changing seasons, slowly unfolding, and what they cause us to remember about the past. Written in various essays and on various drawings is her direct question, “Have you got the time?”

—Marie Warsh

Works

Some Days in April (Poster)

Ink, watercolor, pencil, pastel, and collage on paper

23.5 × 17.5 inches; 26.5 × 20.75 inches (framed)

1978

Poster for Some Days in April

Printed poster

21.75 x 17.24 inches; 24.75 x 20.25 inches (framed)

1978

Connections

Colored pencil, ink, and pastel on paper

19.75 × 25.75 inches; 22.75 × 28.75 inches (framed)

1978

Connections

Colored pencil, graphite, and ink on paper

19.75 × 25.75 inches; 22.75 × 28.75 inches (framed)

1978

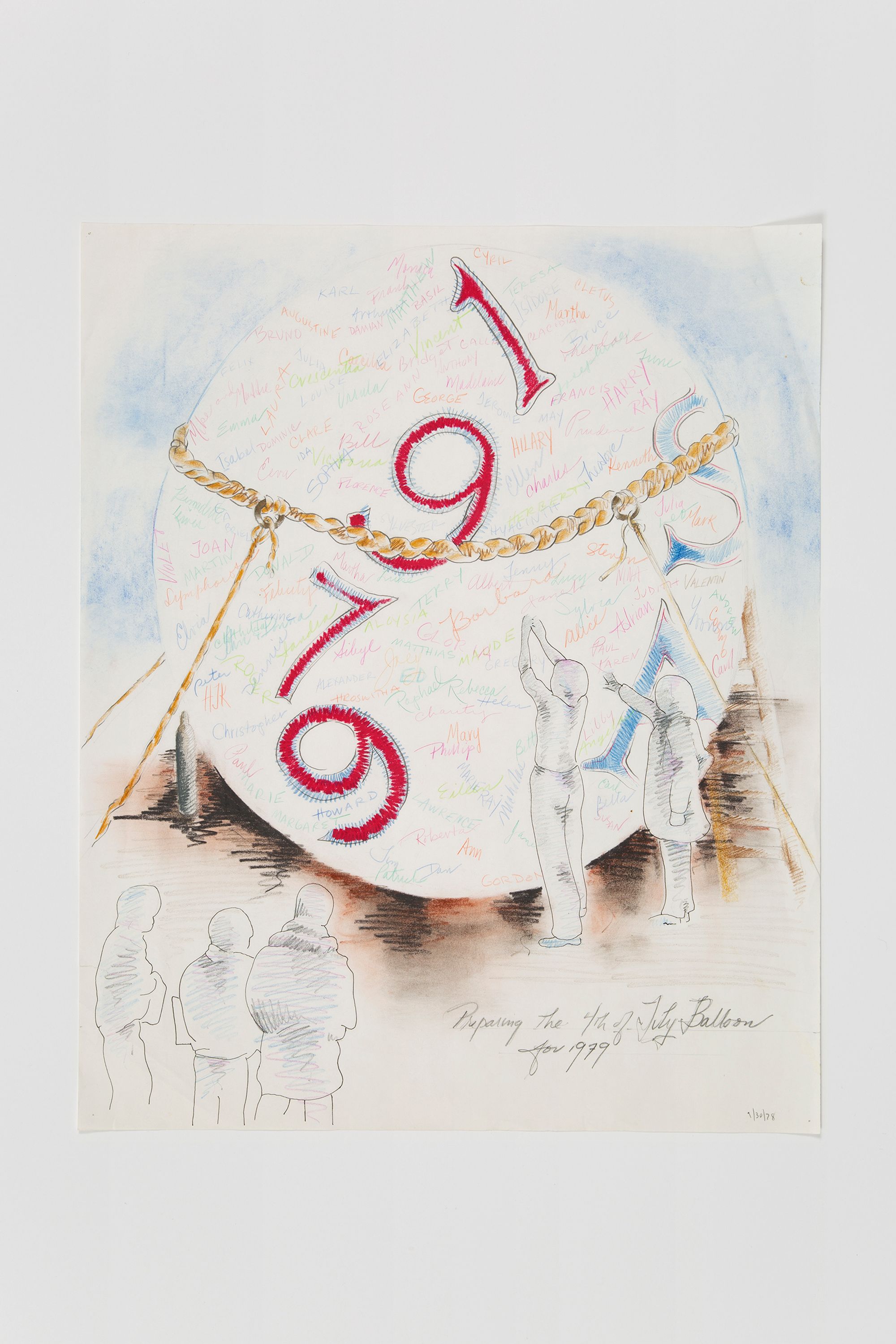

Preparing the 4th of July Balloon for 1979

Colored pencil, graphite, ink, and pastel on paper

17.5 × 14.5 inches; 20.5 × 17.5 inches (framed)

1978

Some Days in April

Colored pencil, ink, graphite, pastel, and watercolor on paper

23.5 × 17.75 inches; 26.5 × 20.75 inches (framed)

1978

Publications

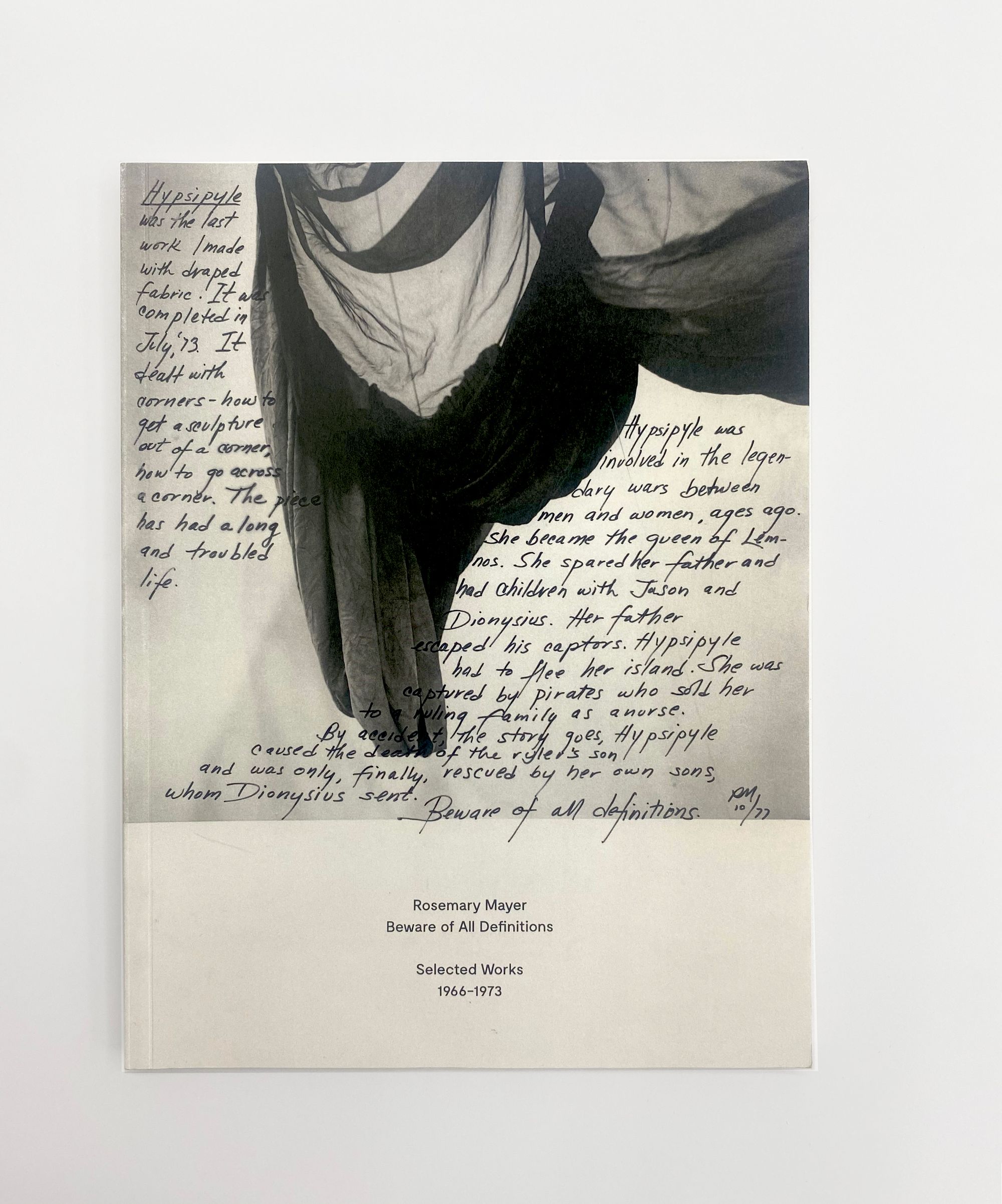

Beware of All Definitions, Selected Works 1966-1973

2017

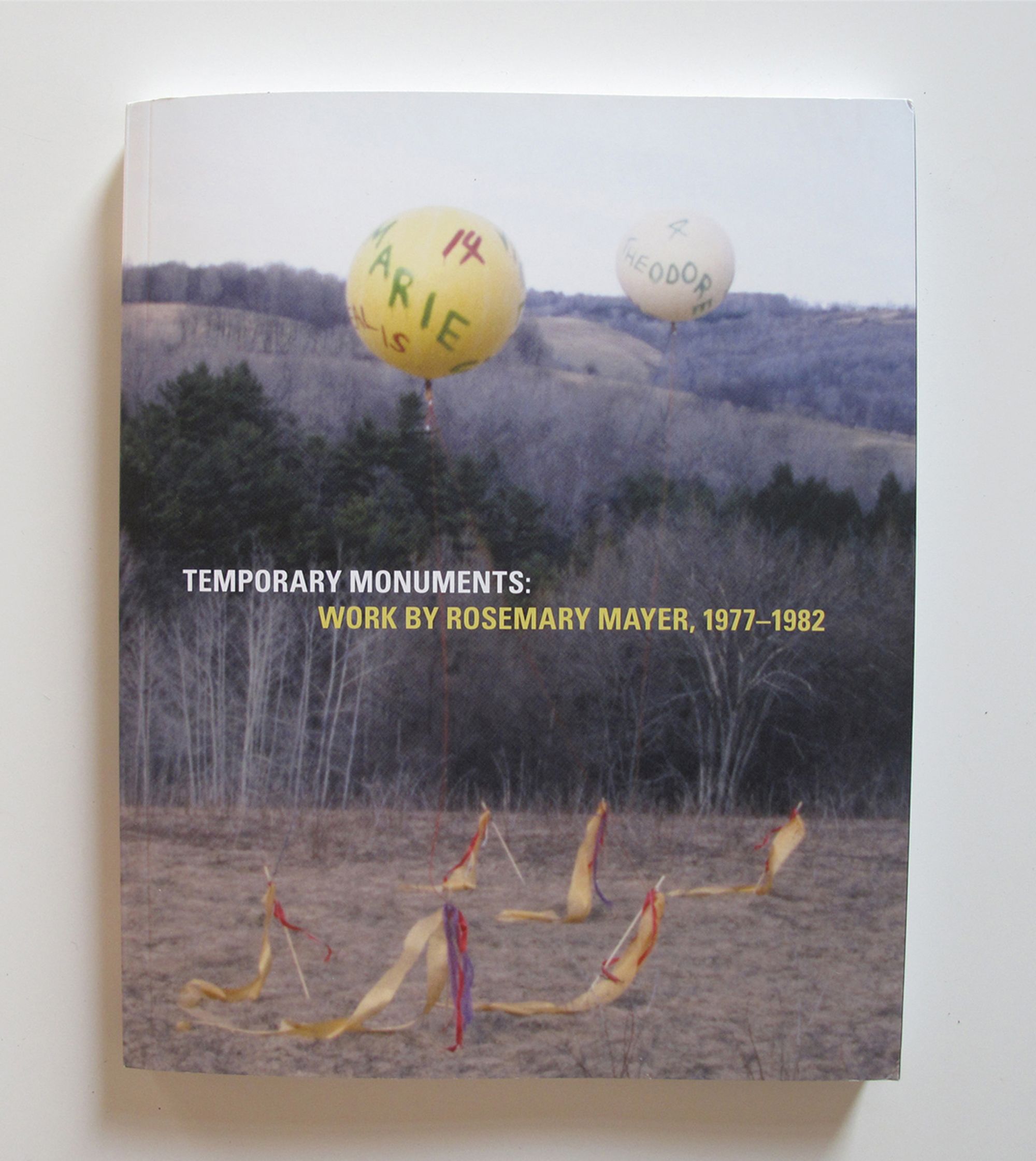

Temporary Monuments: Work by Rosemary Mayer, 1977-1982

2018

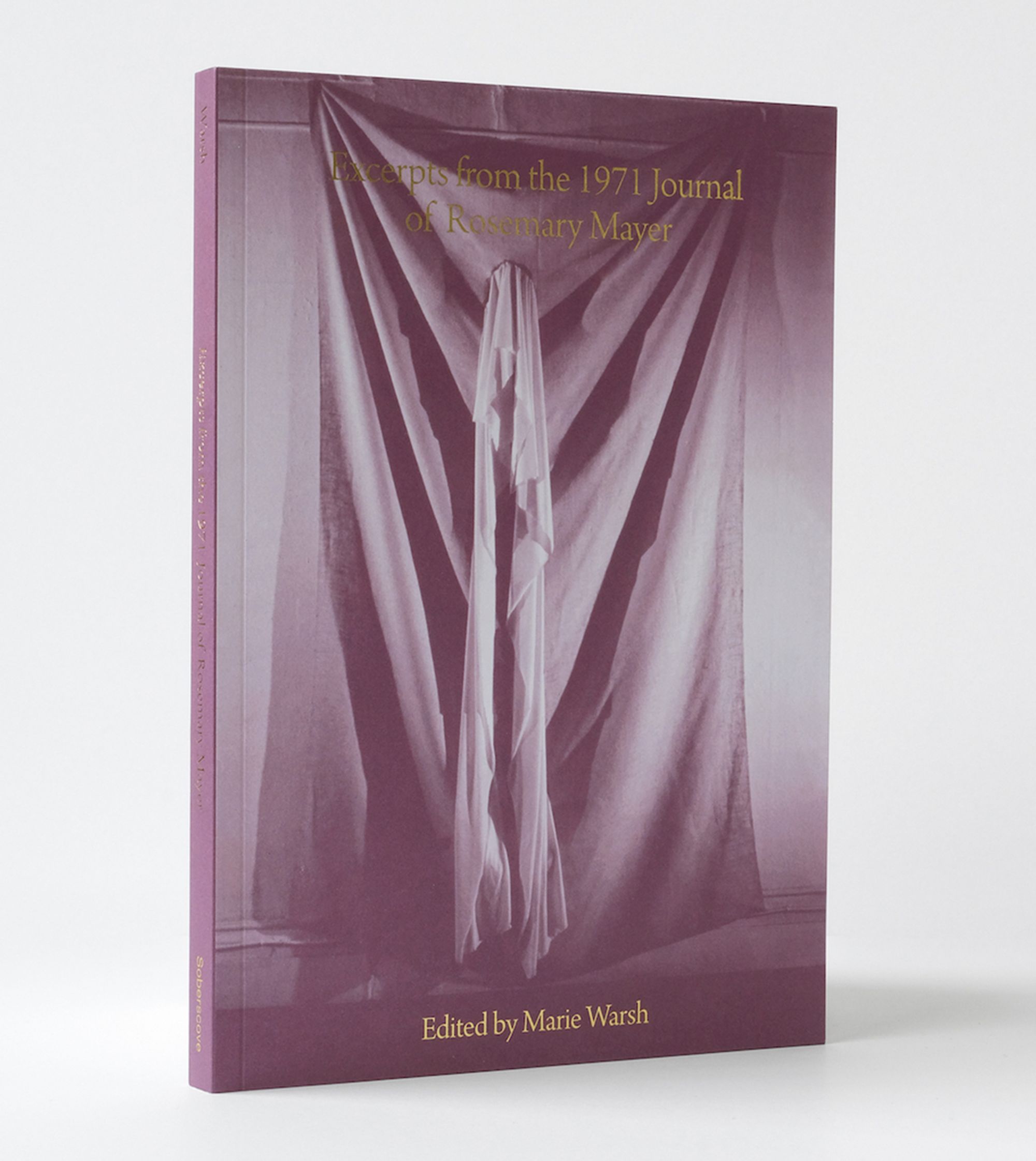

Excerpts from the 1971 Journal of Rosemary Mayer

2020